A 44-Year-Old Man with Knee Pain without Injury

January 18, 2017

A forty-four-year-old man presented to our institution with a two-month history of right medial knee pain and a mild effusion without inciting injury. The patient reported that the pain had gradually worsened after an episode of running. The pain was exacerbated with running or other high-impact activity.

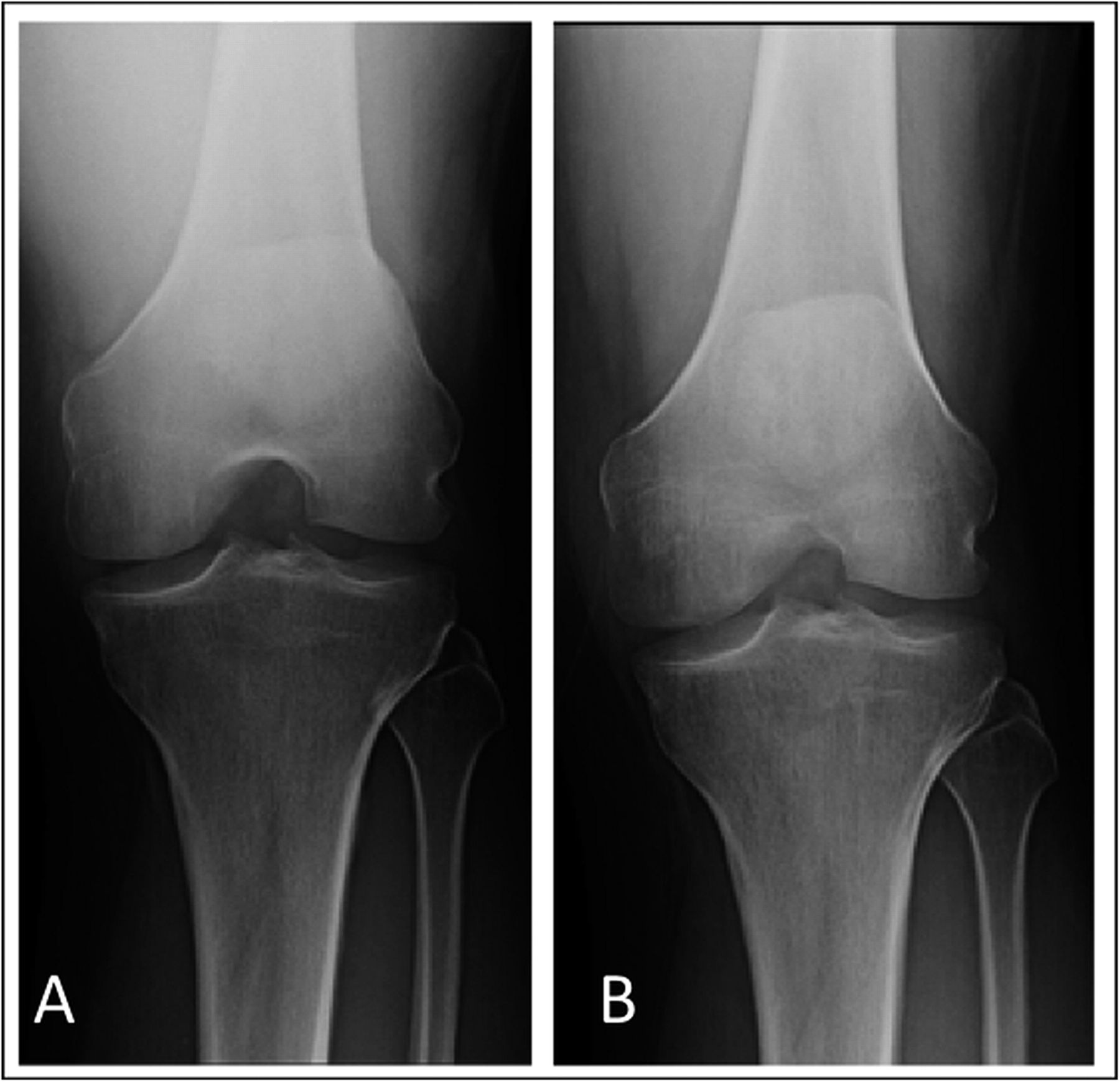

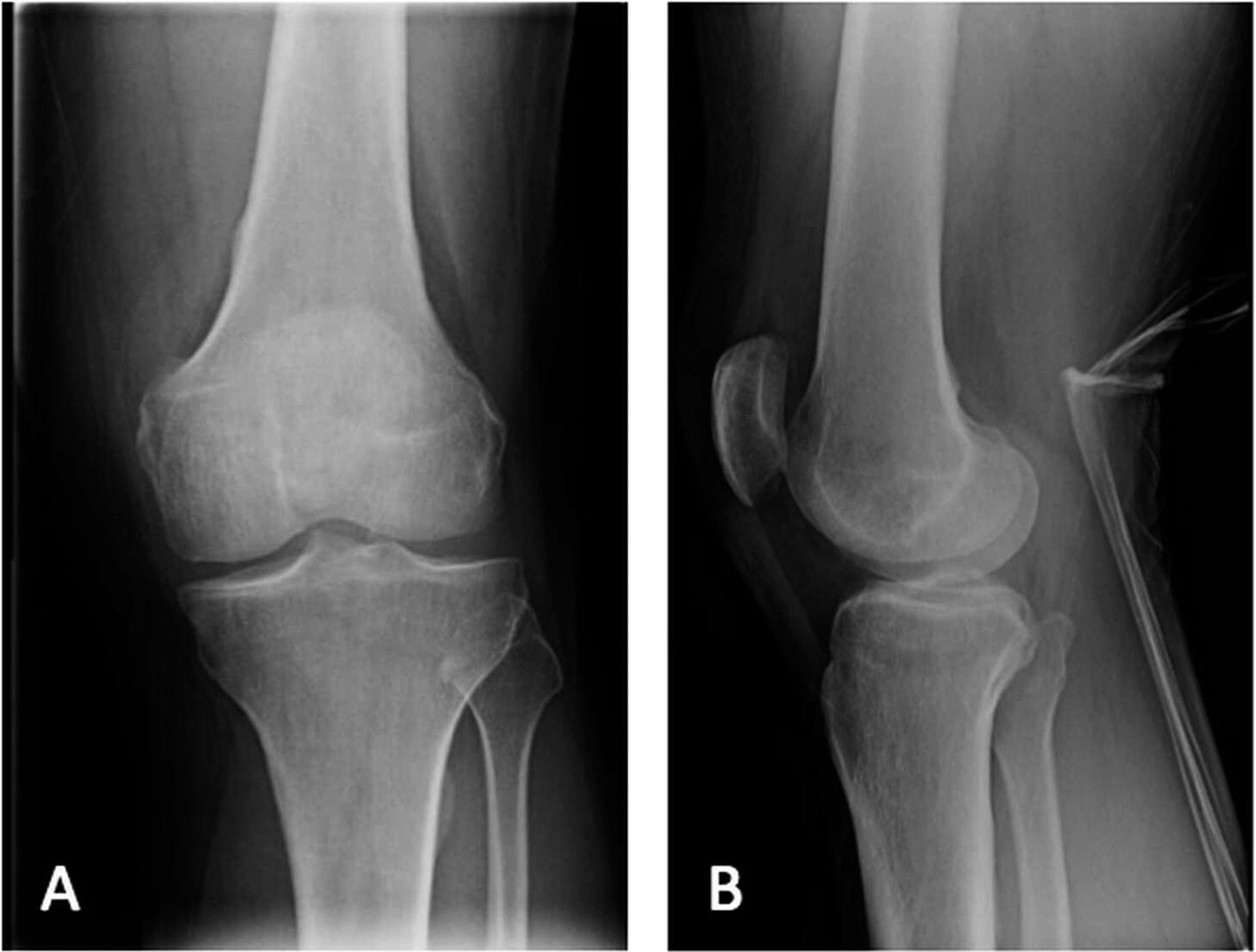

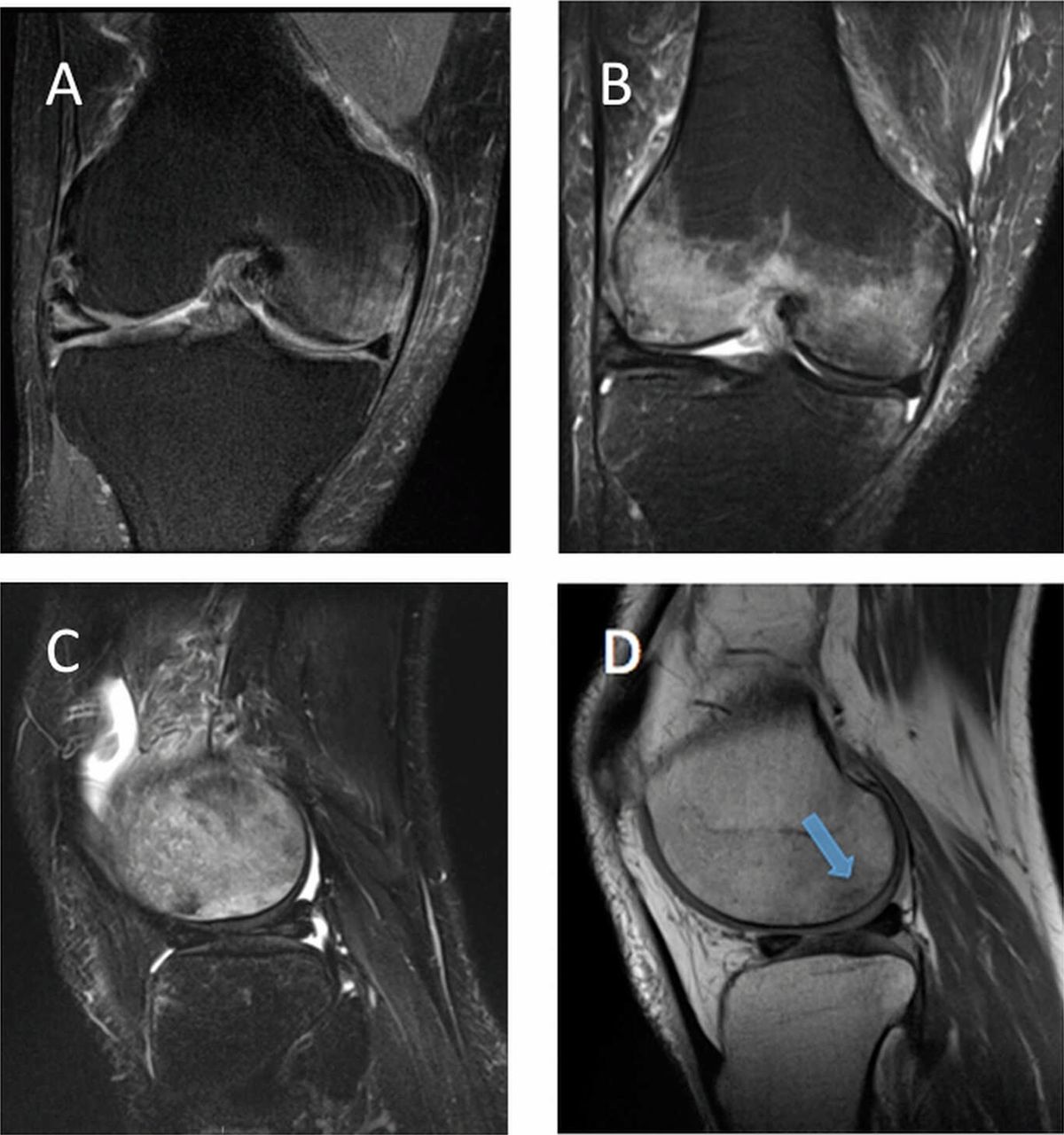

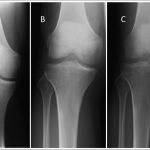

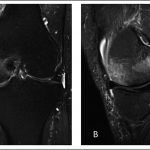

The patient had been evaluated and managed with prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and partial weight-bearing by another orthopaedist, who ordered a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation of the right knee (Fig. 1-A) and referred the patient to our institution. Initial radiographs of the right knee were unremarkable (Fig. 2-A). The patient was managed with partial weight-bearing and a medial unloader brace.

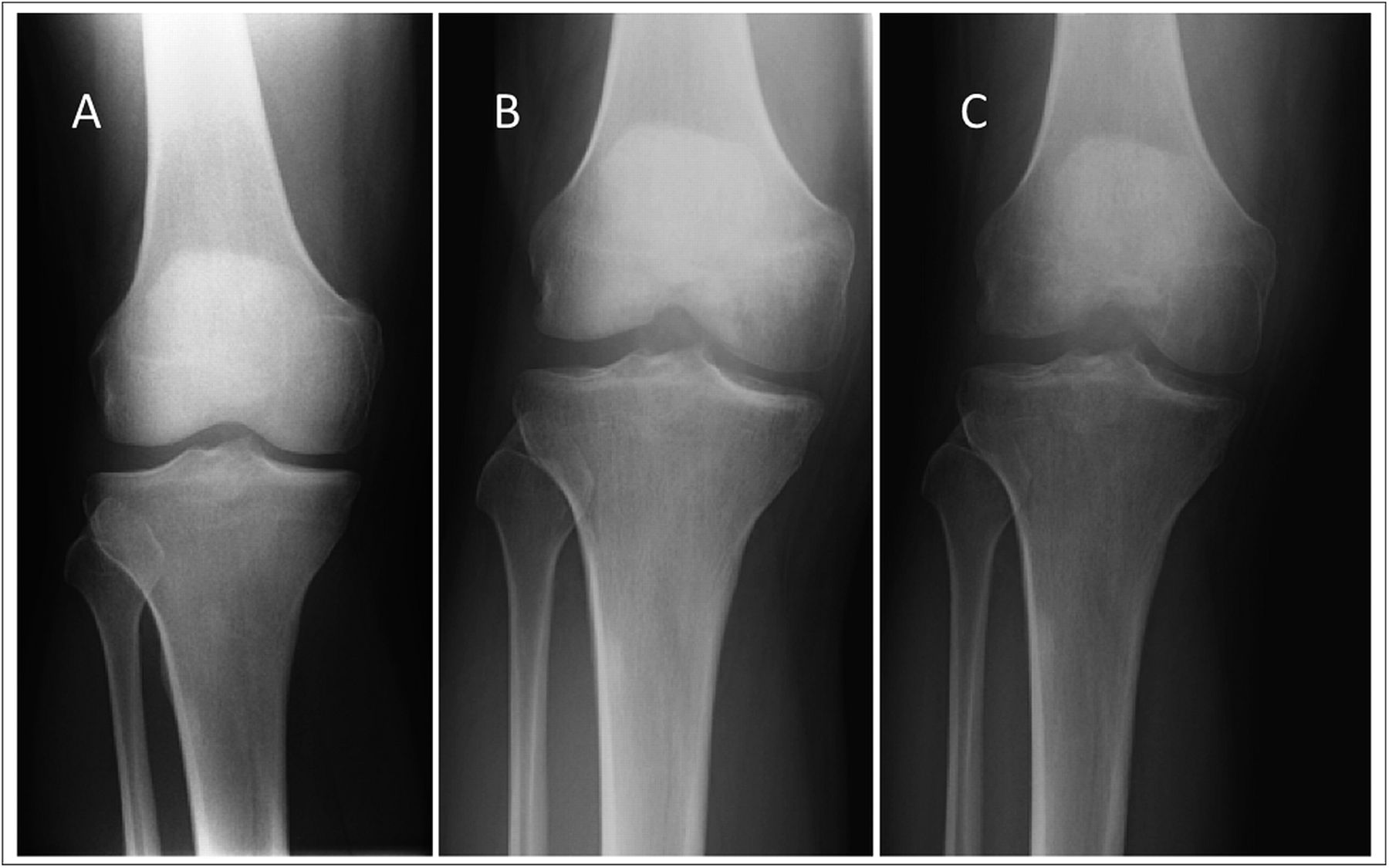

The patient returned for follow-up one month later with a reduction of pain in the right knee; however, the range of motion was decreased (10° to 120°) and a moderate effusion had developed in the right knee. Subsequent radiographs, made two months after the initial radiographs, demonstrated focal osteopenia in the medial femoral condyle (Fig. 2-B). The patient progressed to full weight-bearing with the unloader brace. He was also given a prescription for physical therapy and vitamin-D supplements (3000 IU per day).

Six weeks later, the range of motion had improved; however, the patient reported posterolateral knee pain that was worse with weight-bearing. Radiographs demonstrated persistent osteopenia in the medial femoral condyle with interval development of osteopenia in the lateral femoral condyle and medial tibial plateau (Fig. 2-C). A dual x-ray absorptiometry scan demonstrated normal bone density with no osteopenia or osteoporosis.

On the basis of the clinical history and imaging findings, the diagnosis was bone marrow edema syndrome.

Given the persistence of symptoms over a period of six months despite nonoperative treatment, the patient was offered the option of subchondral drilling of the medial femoral condyle of the right knee.

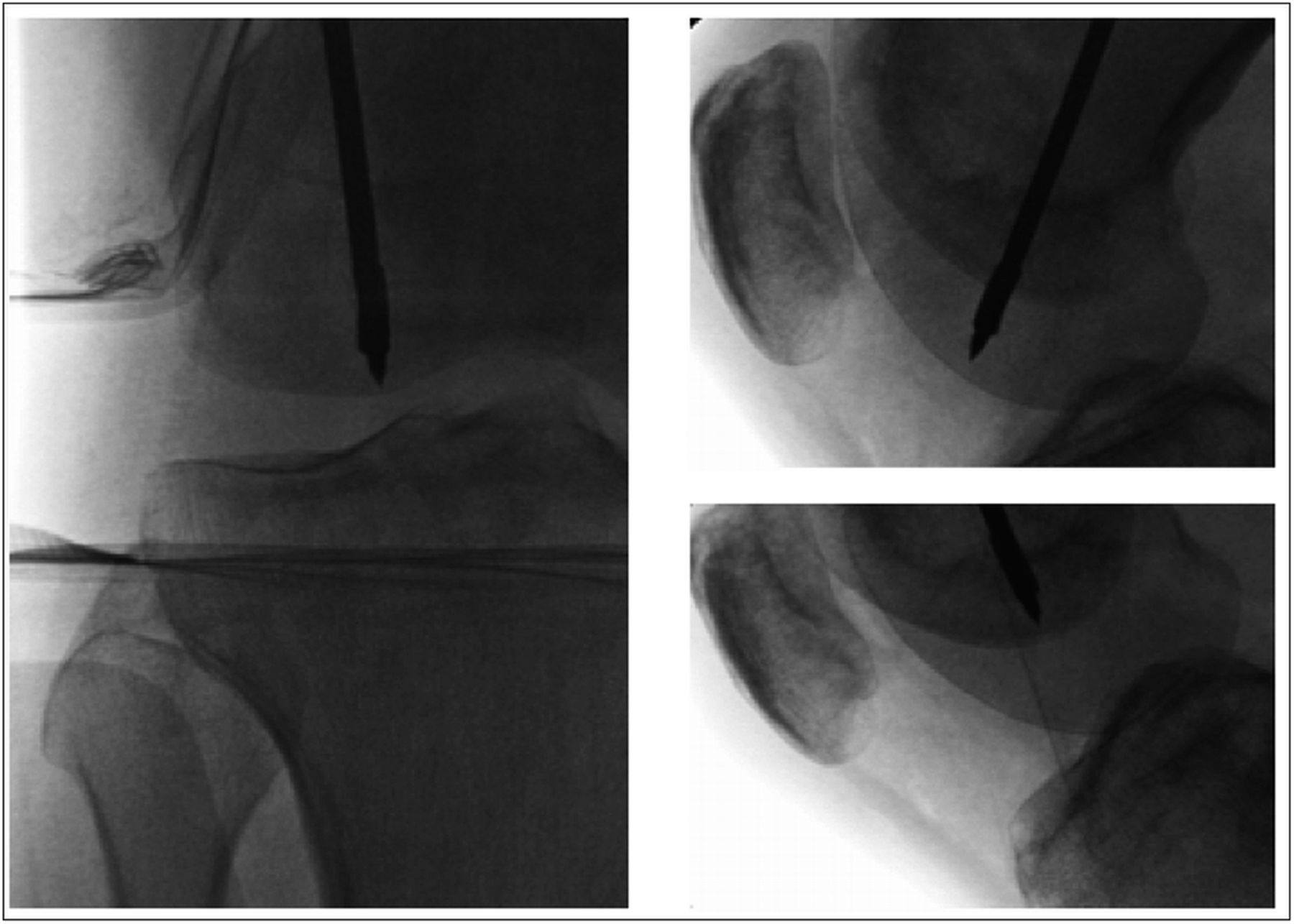

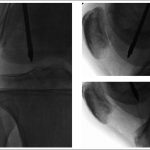

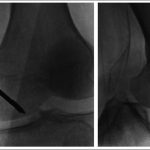

Subchondral drilling of the medial femoral condyle was performed under fluoroscopic guidance with use of a 2.4-mm guide-pin and a 4.5-mm cannulated drill. A total of three channels were created in the medial femoral condyle. Four more channels were created in the lateral femoral condyle with use of the same method (Fig. 3). Arthroscopic visualization of the medial and lateral femoral condyles was performed during drilling to ensure that no violation of the articular cartilage occurred. A partial lateral meniscectomy was performed concomitantly.

The patient was restricted to 50% weight-bearing for one month after surgery and was allowed to return to full activities by two months. The patient had complete relief of symptoms and had returned to full activities by three months.

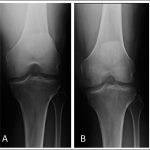

Twenty months after the onset of symptoms in the right knee, the patient began to experience pain in the medial aspect of the left knee that was worse with weight-bearing. Initial radiographs of the left knee were unremarkable (Fig. 4-A). Bracing, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and physical therapy were prescribed.

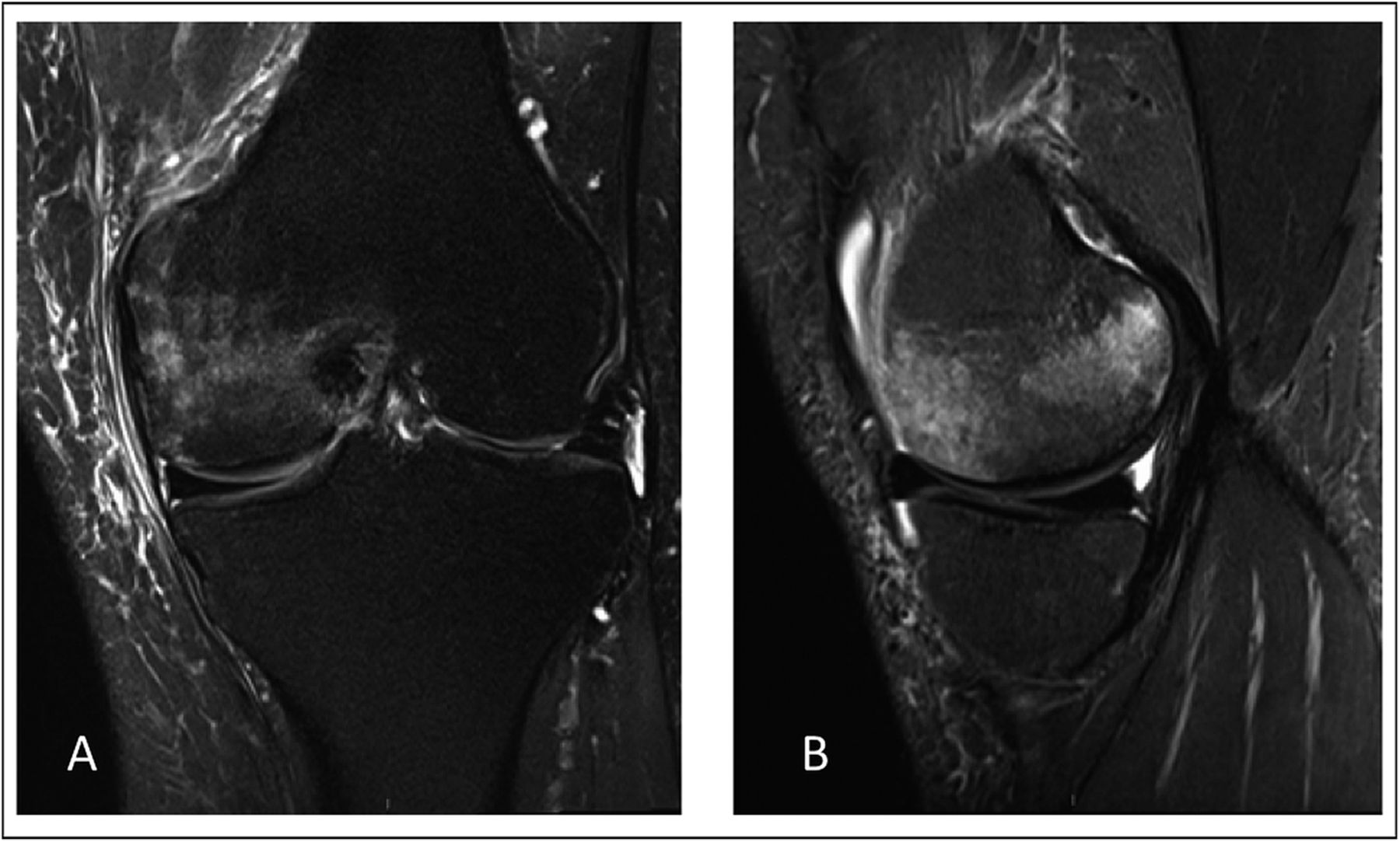

Two months later, radiographs demonstrated focal osteopenia in the left medial femoral condyle (Fig. 4-B). The patient continued to experience pain in the medial aspect of the left knee and had no improvement after a corticosteroid injection. MRI scans of the left knee, made three months after the onset of symptoms, demonstrated bone marrow edema in the medial femoral condyle as well as a horizontal cleavage tear of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus (Fig. 5).

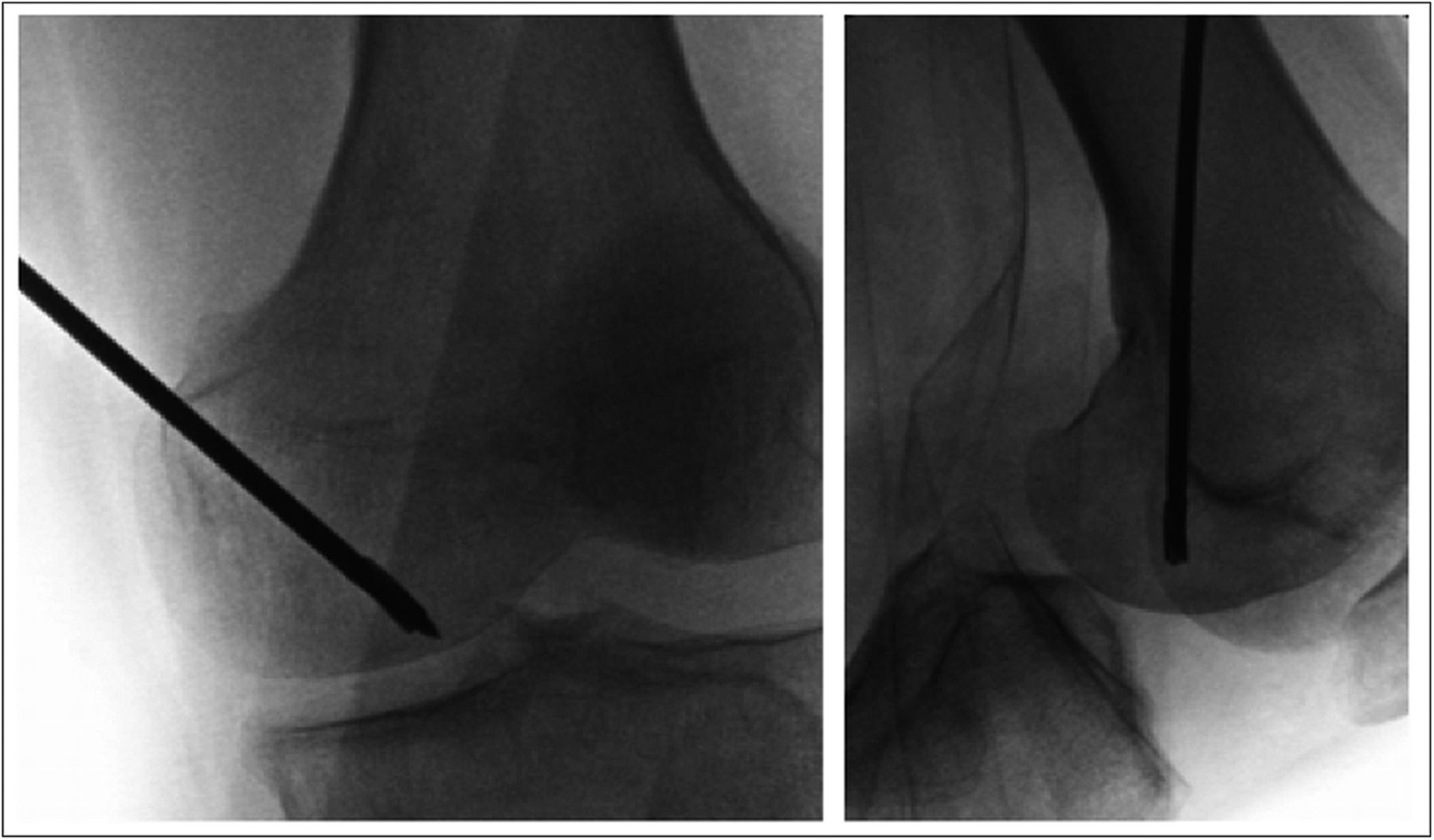

As the symptoms had persisted despite conservative therapy for a total of five months, the patient underwent subchondral drilling of the left medial femoral condyle; the drilling was performed under fluoroscopic guidance with use of a 2.4-mm guide-pin and a 4.5-mm cannulated drill. A total of four channels were created (Fig. 6). A partial lateral meniscectomy was performed concomitantly.

Two weeks postoperatively, the pain in the medial side of the left knee had completely resolved. The patient began a home exercise therapy program in place of formal physical therapy and was allowed to progress to weight-bearing as tolerated, with return to sports at six weeks postoperatively. At the time of the most recent follow-up, nine months after the operation on the left knee, both knees had a full range of motion, no effusion, and no tenderness. At that time, radiographs of the left knee demonstrated full resolution of osteopenia and normal bone density (Fig. 7).

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: Miranian D, Lanham N, Stensby JD, Diduch D. Progression and treatment of bilateral knee bone marrow edema syndrome: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2015 May 13;5(2):e39.

Bone marrow edema syndrome within different compartments of the same knee has been reported in only a small number of patients. Only two cases were reported in a series of twenty-four patients who underwent core decompression of the knee. Even fewer cases have been noted to affect the contralateral knee. Similarly, only a few cases of bone marrow edema involving different compartments of the same knee with migration to the contralateral knee have been treated with core decompression.

The clinical presentation and imaging findings described in the present report are consistent with those described in previous reports on bone marrow edema syndrome. The development of bone marrow edema syndrome has been described as following three phases of progression. The first phase, which is characterized by rapidly progressing pain that can lead to functional disability, frequently lasts approximately one month. The second phase, which is marked by pain that plateaus in intensity, usually lasts one to two months; during this phase, osteopenia may be present on radiographs and typically encompasses a large area. The third phase, which is marked by regression of symptoms and reconstitution of bone density on radiographs, has been reported to last approximately four months. The mean interval between the onset of symptoms and complete clinical resolution of bone marrow edema syndrome has been reported to range from four to twenty-four months (average, six months).

MRI studies demonstrate bone marrow edema, low signal intensity on T1-weighted images, and high signal intensity on STIR (short-tau inversion recovery) or fat-suppressed T2-weighted images. This edema pattern is seen in association with both reversible and irreversible lesions. Nevertheless, there are distinct MRI findings that suggest reversibility, the hallmark of bone marrow edema syndrome. Lack of additional subchondral changes other than bone marrow edema on both T2-weighted and contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images has a positive predictive value of as high as 100% for transient lesions.

Distinguishing bone marrow edema syndrome from other clinical diagnoses such as osteonecrosis—specifically, spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee—relies on the presence or absence of radiographic and MRI findings. Whereas the radiographic osteopenia that is associated with bone marrow edema syndrome typically encompasses a large geographic area, subchondral insufficiency fractures typically involve smaller and more focal areas. The presence of a subchondral area of low signal intensity that is at least 4 mm thick on either T2-weighted or contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images has a strong positive predictive value for irreversible lesions such as the insufficiency fracture seen in association with osteonecrosis. In addition, the presence of abundant new-bone formation leading to the resolution of bone marrow edema syndrome stands in sharp contrast to the irreversible findings that occur in association with osteonecrosis.

While bone marrow edema syndrome presents a unique spectrum of clinical and radiographic features, its pathophysiology remains obscure. There have been several proposed mechanisms for the etiology of bone marrow edema syndrome. Electromyographic findings that are indicative of denervation corresponding with episodes of bone marrow edema syndrome (in terms of both time and location) have given credence to the hypothesis that proximal nerve root pathology is a possible pathologic mechanism of the syndrome. Ischemic events in the small vessels proximal to the nerve roots may be the cause of the disease, with restoration of blood flow in the nerve roots and nerve regeneration being responsible for the clinical course of bone marrow edema syndrome. Histologic findings of dilated sinuses in animal studies demonstrating osteonecrosis occurring in the setting of elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor have led to the hypothesis that hypofibrinolysis is a cause of bone marrow edema syndrome. Intraosseous hypertension is another abnormality that may be a component of bone marrow edema syndrome and is characterized by pain secondary to elevated interosseous hypertension and a decreased arteriovenous pressure difference, leading to ischemia. It is possible that the patient described in the present report had some component of intraosseous hypertension that responded favorably to core decompression.

Despite the lack of a well-described and supported pathogenesis for bone marrow edema syndrome, several treatments have been described. Berger et al. reported that core decompression is a treatment option for bone marrow edema syndrome. At five years after surgery, bone marrow edema was not present on MRI. Nonoperative therapeutic strategies consist of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, mild analgesics, partial weight-bearing, short-term non-weight-bearing, calcitonin, prostacyclin analogs, and bisphosphonates.

In the case of the patient described in the present report, the progression of clinical and radiographic findings despite nonoperative treatment ultimately led to bilateral subchondral core decompression for the treatment of bone marrow edema syndrome. At the time of the latest follow-up, the patient had had a complete clinical recovery. Similar to previous reports, this case demonstrated that subchondral core decompression can be effective for the treatment of bone marrow edema syndrome. The case described here represents a single instance of bilateral multicompartmental bone marrow edema syndrome of the knee that responded favorably to subchondral core decompression. However, the results for this patient should be considered within the context of the existing literature.

Reference: Miranian D, Lanham N, Stensby JD, Diduch D. Progression and treatment of bilateral knee bone marrow edema syndrome: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2015 May 13;5(2):e39.

What is the diagnosis?

Osteochondritis dissecans

Compression fracture

Osteonecrosis (avascular necrosis)

Bone marrow edema syndrome

Osteomyelitis

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3 Fig. 4

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

Fig. 5 Fig. 6

Fig. 6 Fig. 7

Fig. 7