A 32-Year-Old Woman with Pain in a Previously Broken Wrist

August 4, 2021

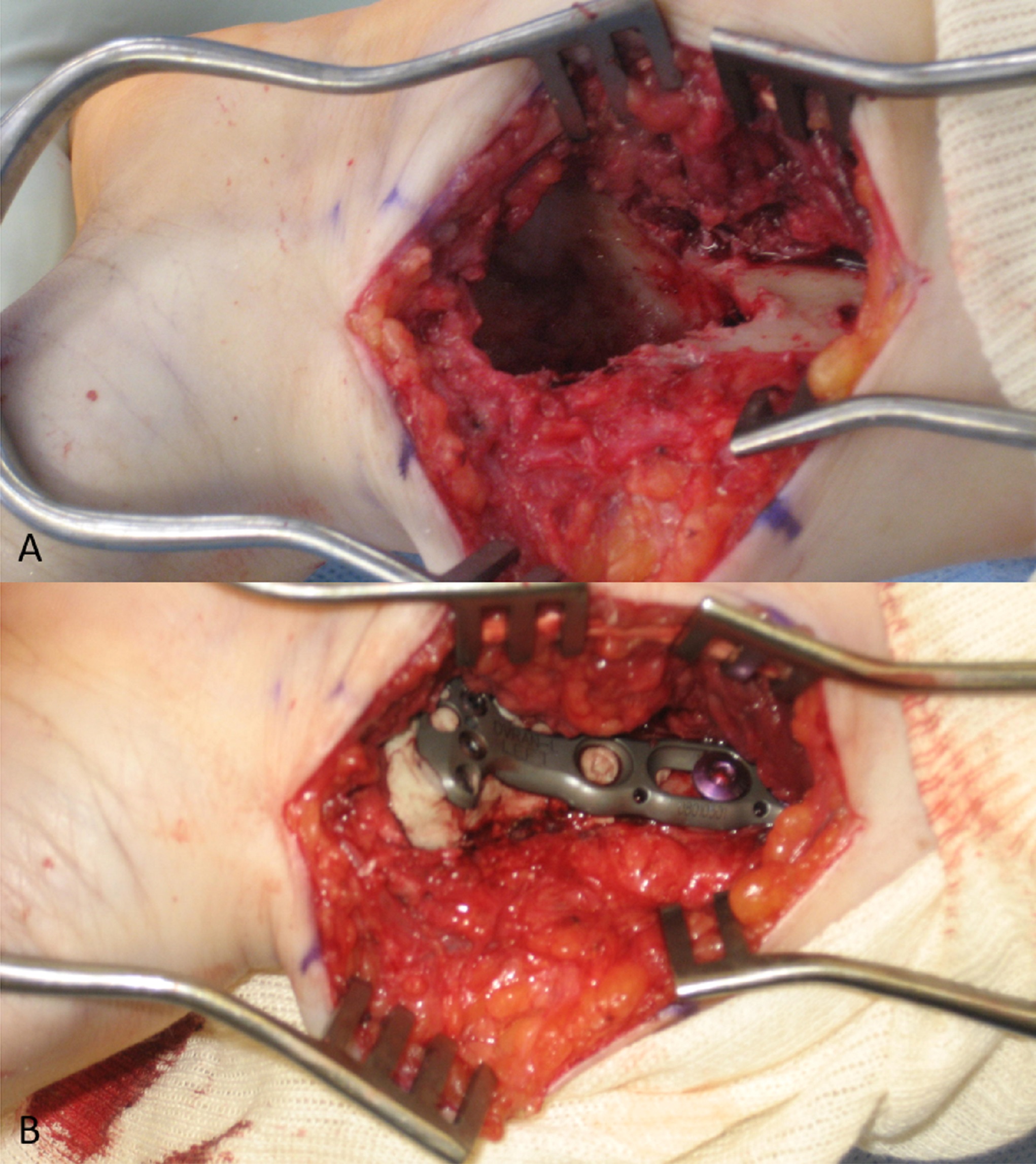

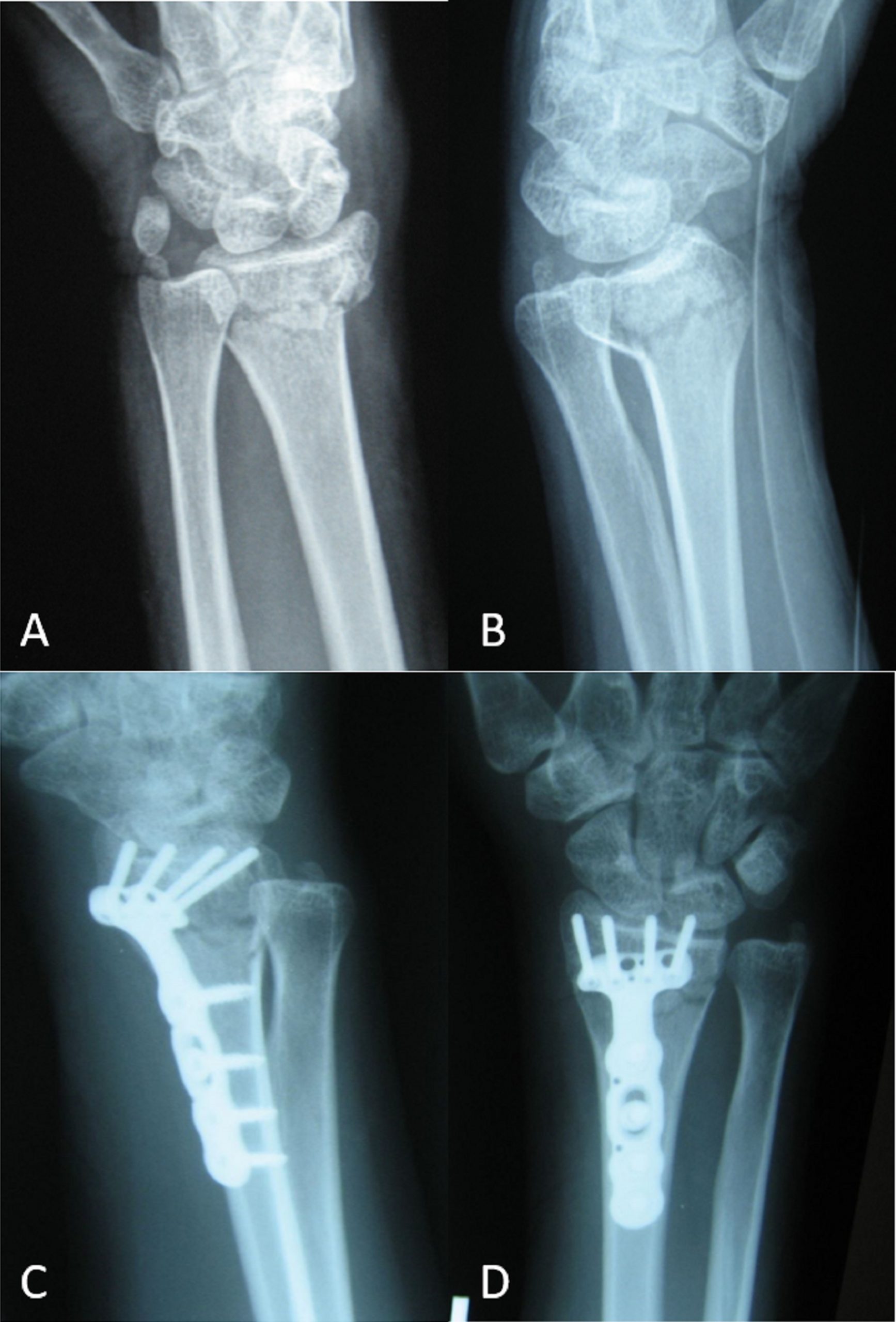

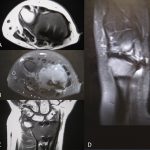

A 32-year-old woman experienced a distal radial fracture of the left wrist after trauma 6 years before presentation. At that time, she was found to have a displaced, extra-articular distal radial fracture without any evidence of an underlying lesion (Figs. 1-A and 1-B). She was treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) through a standard volar approach. There were no complications from the surgical procedure, and the postoperative course was unremarkable. Approximately 6 years later, when the patient was then about 10 weeks pregnant, she fell at her home after having had pain relief up until this event. After the fall, she presented with left wrist pain similar to when she initially fractured the wrist. No fracture was noted on radiographic evaluation, but a lesion was noted to have developed, possibly associated with the implant (Figs. 2-A and 2-B).

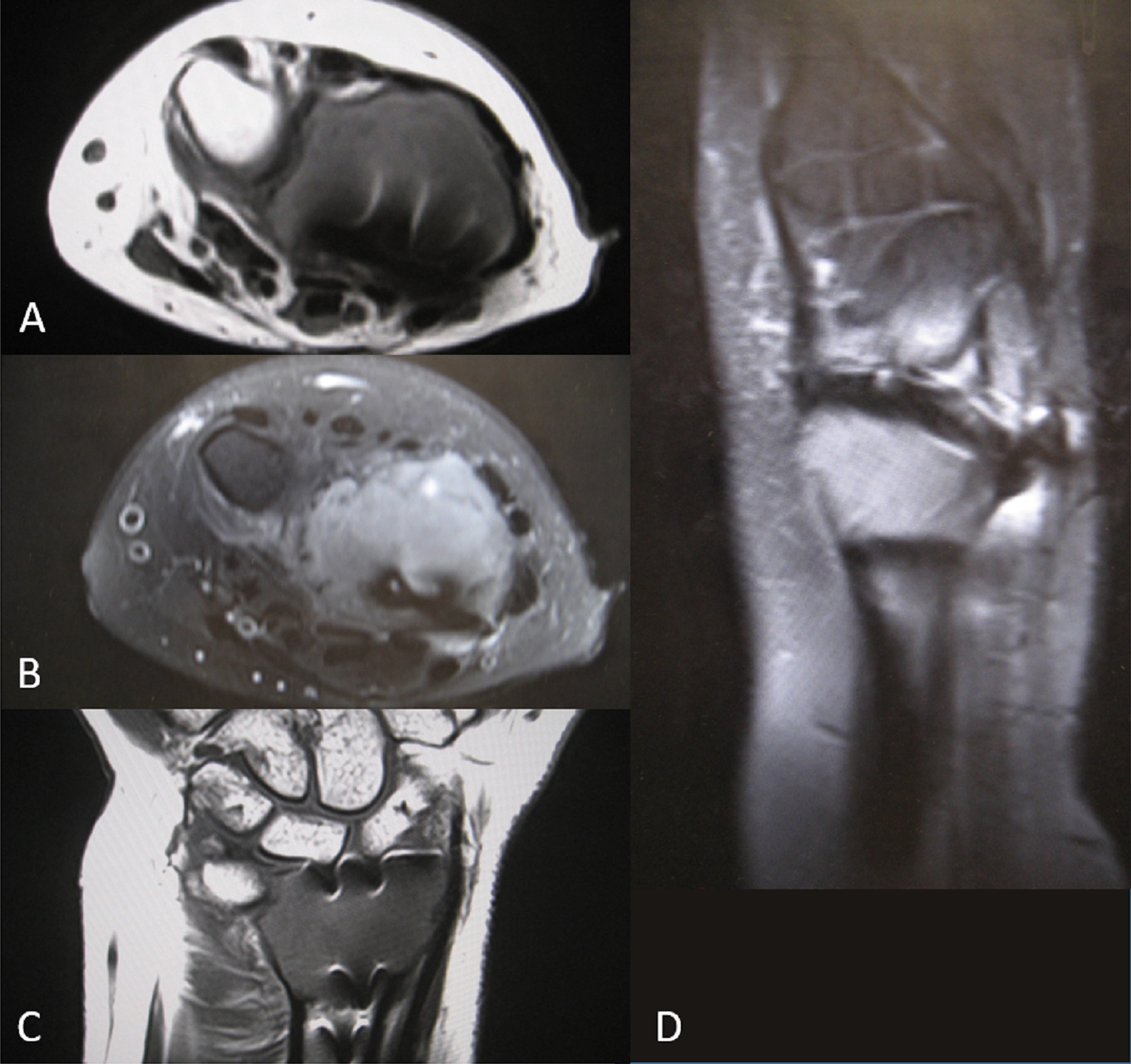

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left distal part of the radius revealed extensive bulging of the cortex dorsally but no definite soft-tissue mass (Figs. 3-A through 3-D). The plan was to perform a procedure to remove the implant, obtain a frozen section to rule out malignancy, and perform intralesional curettage and fill the defect with bone cement.

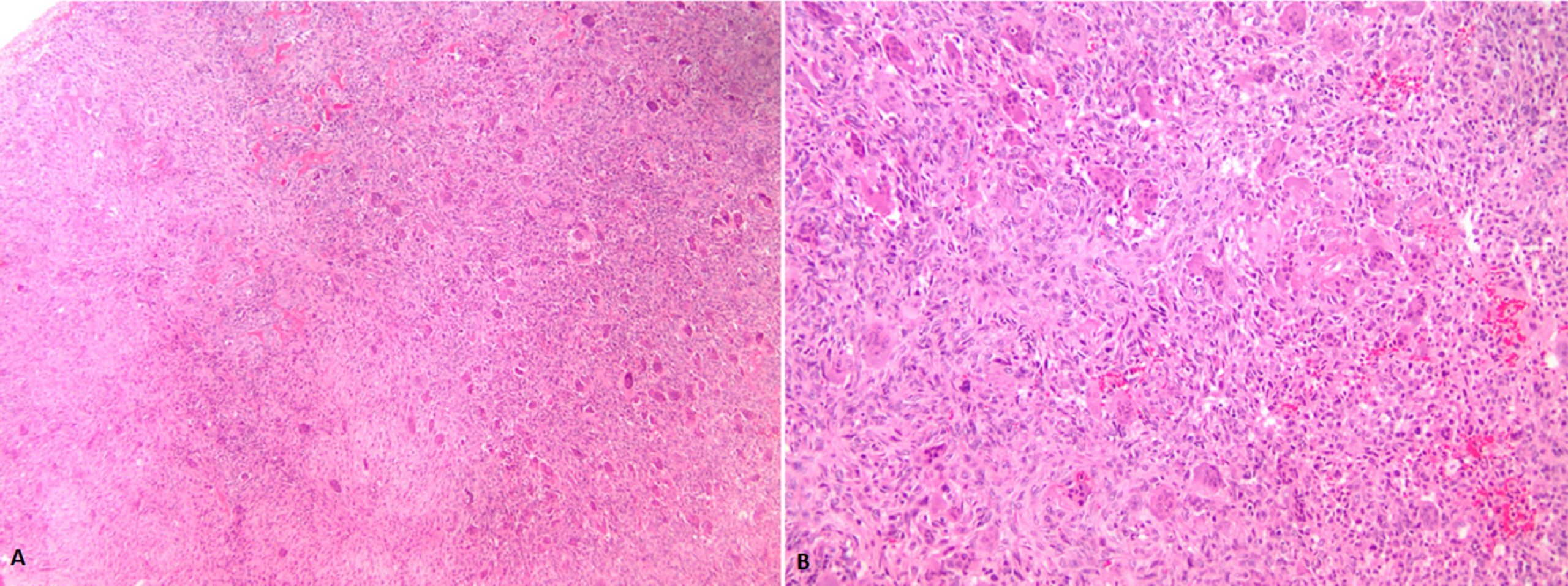

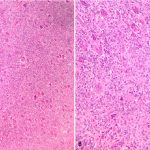

Due to her pregnancy, obstetrics was consulted, and the patient received an axillary block for the procedure. The previous incision was used on the volar distal part of the radius. The plate was removed, and a frozen section was obtained. Of note, one screw was broken and the remaining piece was not able to be removed easily. Histology from the frozen section and the subsequently curetted lesion is shown in Figures 4-A and 4-B.

The uniform distribution of osteoclast-type giant cells and mononuclear cells was interpreted as a giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone.

After removal of all of the implant, the distal part of the radius was opened widely on the volar aspect and all of the visible lesion was curetted (Fig. 5-A). A high-speed burr was then used to burr the entire cavity, removing all the cancellous bone to the cortical surface. The tumor was also removed from the radial styloid. Once the tumor was removed, bone cement was placed in the remaining cavity. A plate was placed using 2 screws proximally to span the defect (Fig. 5-B).

Two years postoperatively, radiographs demonstrated a well-fixed distal part of the radius with intact implant and bone cement without any signs of tumor recurrence (Fig. 6). The patient had experienced pain relief and was doing well and back to her normal activities.

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: Siesel C, Muhammad B, Weiner S. Giant cell tumor after distal radius open reduction and internal fixation in a pregnant woman: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020 Jul-Sep;10(3):e20.00165.

GCTs of the bone are benign, locally aggressive tumors with osteolytic properties. The receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB) ligand–receptor activator of NF-kB–osteoprotegerin (OPG) (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand [RANKL]-receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B [RANK]-OPG) pathway is closely involved with the pathogenesis of GCT, leading to increased bone resorption. Osteoblasts produce RANKL, which binds to RANK on osteoclast precursors and stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption. OPG plays an important role by preventing RANKL from binding with RANK and thus protects the skeleton from excessive bone resorption via RANKL-RANK interaction. In GCT, there is an increased ratio of RANKL to OPG, which leads to increased bone resorption.

The diagnosis of GCT requires histological confirmation, with visualization of osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells and mononuclear cells within a pathological bone lesion. GCT of bone may present with a pathologic fracture because of cortical bone disruption, which is then exacerbated by local trauma. If there is any concern for a pathologic cause of any fracture, representative tissue should be submitted for pathology.

Our patient presented when she was 10 weeks pregnant. Although no specific association between GCT and pregnancy has been established, there are several case reports of GCT arising during pregnancy, and some tumors have been found to express estrogen receptors. However, these instances may simply be linked to the demographic characteristics of the disease because GCT is more common in women in their twenties and thirties. It was difficult to determine the timing of the development of GCT in this patient and her pregnancy. More research needs to be done to advance any theory of correlation between GCT and pregnancy.

This case also presented the unique scenario of GCT at the site of a previous fracture with an implant. At her initial surgical procedure, there was no evidence of GCT of the distal part of the radius, and the GCT of the distal part of the radius was not discovered until 6 years later, suggesting that the GCT likely developed after fixation of the distal radial fracture. There are only a few other case reports of a GCT arising after a fracture. In this patient, GCT occurred long after the initial fracture, raising the potential for association, but, currently, there is no known link between GCT and fracture or pregnancy.

Reference: Siesel C, Muhammad B, Weiner S. Giant cell tumor after distal radius open reduction and internal fixation in a pregnant woman: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020 Jul-Sep;10(3):e20.00165.

What is the diagnosis?

Giant cell reparative granuloma

Giant cell tumor of bone

Adverse local tissue reaction to metal particles

Aneurysmal bone cyst

Brown tumor of hyperparathyroidism

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3 Fig. 4

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

Fig. 5 Fig. 6

Fig. 6