A 59-Year-Old Man with a Rapidly Growing Thigh Mass

July 1, 2020

A 59-year-old man was referred by his family doctor with a history of a painful mass on the anteromedial aspect of the left thigh. The patient noticed that the mass had doubled in size over the course of 4 months. He reported no limitations in activity and there was no history of antecedent trauma to the area. The patient reported that he had not had any constitutional symptoms. He had no important medical or relevant family history.

Physical examination of the left thigh revealed a hard and mobile mass that was tender on palpation of the anteromedial aspect of the left femur distally. No associated signs of infection were observed. Neurologically, there were no motor or sensory deficits. Distal pulses were palpable, and the patient’s ipsilateral knee demonstrated a full range of motion. We did not observe lymphadenopathy or other masses.

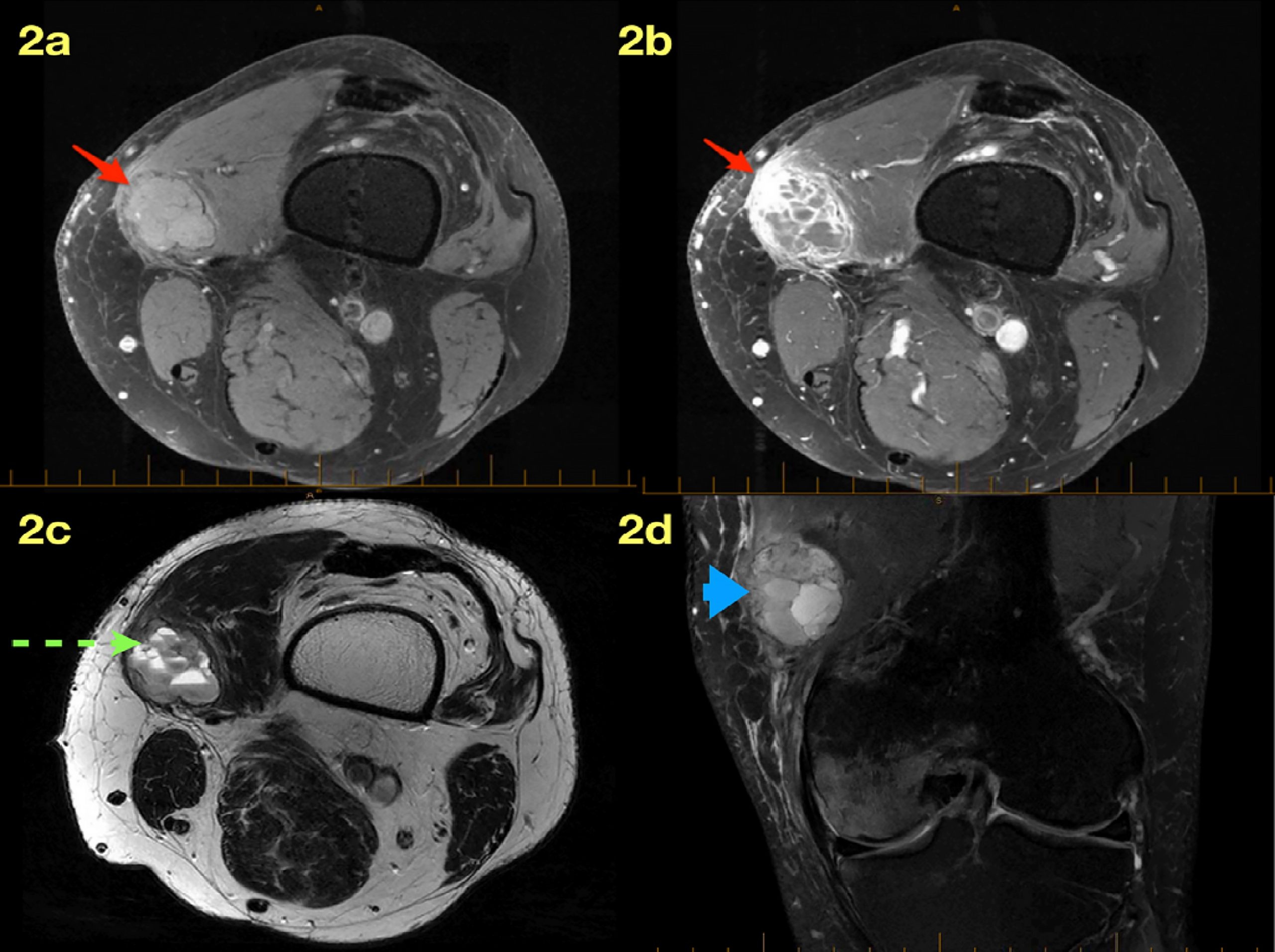

Radiographs of the left femur demonstrated a circumscribed 3.3 × 3 cm mass with a peripheral rim mineralization within the area of the vastus medialis muscle (Fig. 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a well-encapsulated, heterogeneous mass with high-intensity internal septations on T2-weighted imaging (Fig. 2). The lesion was bordered by a low signal intensity mineralized rim on T1-weighted imaging. There appeared to be fluid-fluid levels (Fig. 2-C). There was no bone involvement of the underlying normal bony structures.

Given the history of progressive and rapid enlargement of the mass, we proceeded with a core needle biopsy to rule out soft-tissue sarcoma.

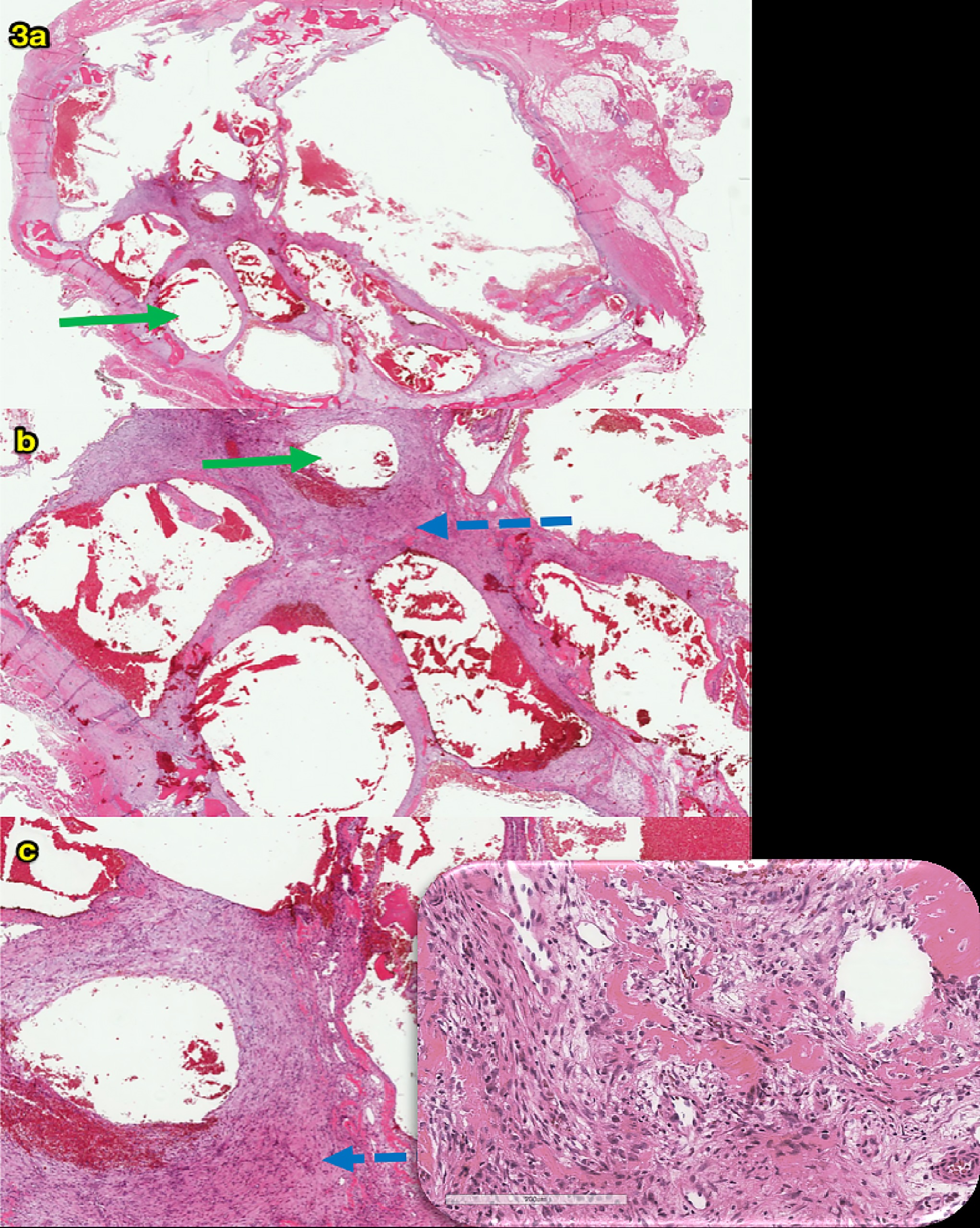

The needle biopsy specimen was interpreted as benign, so a decision was made to perform a complete excision of the soft-tissue mass because of the pain that the patient was experiencing. Surgical dissection showed a well-encapsulated mass, with no extension or attachment to the surrounding (normal) structure; resection of the entire tissue was performed. The resected specimen measured 4.5 × 4.5 × 2.5 cm and it contained red-brown, hemorrhagic soft-tissue fragments. The histology of the lesion is shown in Figure 3.

Based on the histological finding, the diagnosis was interpreted as an extraosseous (soft-tissue) aneurysmal bone cyst. Cytogenetics testing was requested, but the results were inconclusive because of insufficient samples. At the 18-month follow-up, the patient reported no pain and had a full range of motion of the knee. Follow-up radiographs showed no evidence of recurrence.

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: AlAqeel M, Nooh A, Wang CK, Turcotte R. An extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst in a 59-year-old man: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020 May 11;10(2):e0493.

Aneurysmal bone cyst is a common neoplastic lesion that occurs primarily in the metaphysis of long bones, with children and adolescents being most frequently involved. The extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst occurrence is rare. Although it occurs extraskeletally, it shares common clinical and histopathological features with the primary aneurysmal bone cysts. Classically, these tumors are known to occur in the skeletal muscles, subcutaneous tissues, and rare sites including arterial walls and larynx. We report on a 59-year-old man who presented with an extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst. To our knowledge, cases of extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts have been rarely reported in individuals over the age of 40 years.

Age is a critical predicting factor in diagnosing soft-tissue masses because certain age groups are more likely to have specific diagnoses. Our patient was 59 years old, and his presentation was consistent with a neoplastic process. Therefore, it is important to start by doing a complete workup to rule out a malignant lesion. A core needle biopsy was performed initially and was consistent with the extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst. Although uncommon, these tumors can occur in a wider age group (range, 3 to 60 years) compared with osseous aneurysmal bone cyst, where it is more prevalent in the younger population and arises most commonly in the lower extremities. McCann reported a 1.8 × 1 cm ankle mass that progressed slowly, whereas Baker et al. reported a large mass (7 × 7.6 cm) with a rapid progressive course, which is in line with our report.

Radiographically, extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts produce the characteristic fluid-fluid levels and typically do not enhance after gadolinium administration. The classic honeycomb appearance may appear in postcontrast images if a substantial network of septations is present. In addition, if the lesion is mature enough, the mineralized rim that represents immature bone is responsible for the “doughnut” sign that is observed on technetium bone scintigraphy. Despite these classic findings on imaging, it can be confused with a spectrum of other lesions including myositis ossificans, giant cell tumor, and telangiectatic osteosarcoma. In contrast to extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts, myositis ossificans primarily presents with a history of trauma. In the acute stages, myositis ossificans will display T2-weighted hyperintensity due to blood products, granulation tissue, and edema. In mature stages, the pattern of lamellar bone demonstrates a low-signal intensity in all sequences with areas of intralesional fatty morrow. It can be challenging to differentiate giant cell tumors from extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts, in part because both can contain large numbers of giant cells. Extraosseous osteosarcoma appears as a soft-tissue density with central mineralization separated with a distinctive pseudo-capsule from adjacent structures. The differentiation is critical as their management is completely different. Typically, extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts do not reoccur after surgical excision. We identified only one case in the literature of recurrence in an 8-year-old child after marginal excision that never reoccurred again.

The differentiation of extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts from other differential diagnoses will require histological examination of these lesions. Typically, they are composed of blood-filled cysts separated by septae. These septae are composed of fibroblasts and are surrounded by osteoclast-like giant cells, peripheral reactive bone-like tissues, and woven bone. There are several tumors that could mimic extraosseous aneurysmal bone cysts, including myositis ossificans, giant cell tumor of soft tissue or tendon, nodular fasciitis, ossifying fibromyxoid tumor, and extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Careful clinical, radiographical, and pathological assessment should help in the diagnosis. Cytogenetic analysis is also helpful in confirming the diagnosis in cases where the diagnosis is equivocal. The hallmark for diagnosis is ubiquitin specific protease (USP) 6 rearrangement; however, it may still extend to other lesions such as giant cell tumors of the head and neck.

In summary, we presented a case of an extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst in a 59-year-old man and highlighted the fact that these tumors can occur in any age group. Careful clinical and pathological assessment should be performed to rule out malignancy.

Reference: AlAqeel M, Nooh A, Wang CK, Turcotte R. An extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst in a 59-year-old man: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020 May 11;10(2):e0493.

What is the diagnosis?

Extraosseous giant cell tumor

Extraosseous aneurysmal bone cyst

Myositis ossificans

Clear-cell neoplasm consistent with metastatic renal cell carcinoma

Telangiectatic osteosarcoma

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3