A 29-Year-Old Man with Recurrent Thigh Pain over Three Months

September 5, 2018

A 29-year-old active man presented to the orthopaedic department at an urban hospital in Buenos Aires in July 2014 with new-onset nontraumatic “on-and-off” pain (Numerical Rating Scale [NRS] score, 2 of 10) in the proximal anterolateral aspect of the left thigh. He was afebrile and had no limitation of daily activities; the neurovascular examination was normal. Symptomatic treatment with analgesics was provided, and a follow-up was scheduled for shortly thereafter. He experienced some relief and continued regular activities.

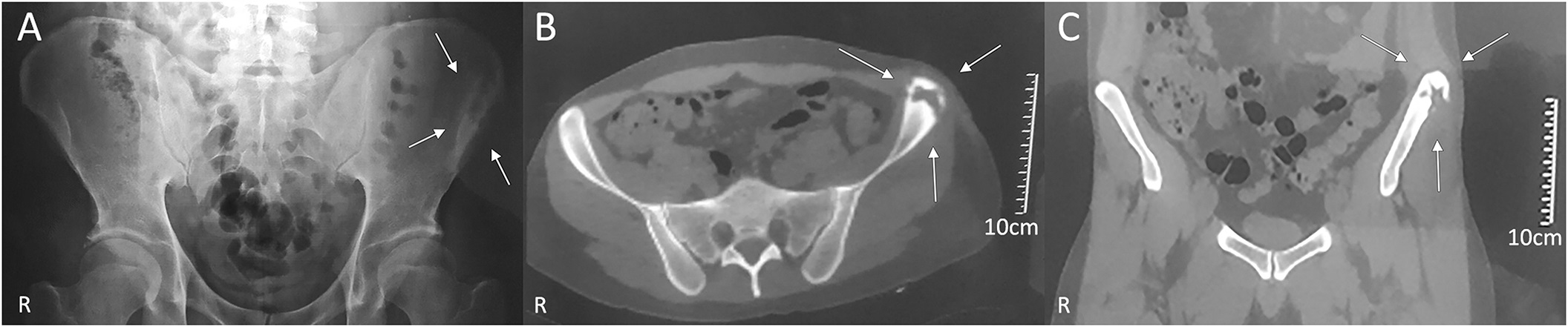

Three months later, by mid-October, he presented to the emergency department after sustaining a fall. He had severe pain (NRS score, 7-8 of 10), an antalgic gait, normal vital signs, and swelling in the anterolateral aspect of the left thigh. Hemoglobin levels and the white blood-cell (WBC) count were normal. An ultrasound revealed a hypoechoic subcutaneous fluid collection with thick irregular borders measuring 70 × 22 mm. Radiographs of the pelvis (inlet and outlet views) showed a bone rarefaction on the left anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). Computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis and the thigh showed an osteolytic lesion, a heterogeneous fluid collection measuring approximately 67 × 20 mm, and ipsilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy (Fig. 1).

A guided fine needle aspiration yielded fluid that was sent for cytologic analysis, Gram staining, and bacterial cultures. Blood cultures were ordered, and the patient was started on clindamycin therapy empirically. He was evaluated by the infectious disease department and the orthopaedic department. A week later, there was persistence of pain (NRS scale, 7 of 10) as well as the recent onset of night sweats and shivers. He was afebrile and had swelling with no erythema; a small access wound oozed a serohematic secretion in the left iliac region. Because he had experienced approximately 3 months of ongoing symptoms, he was referred for evaluation to our orthopaedic institution in Buenos Aires.

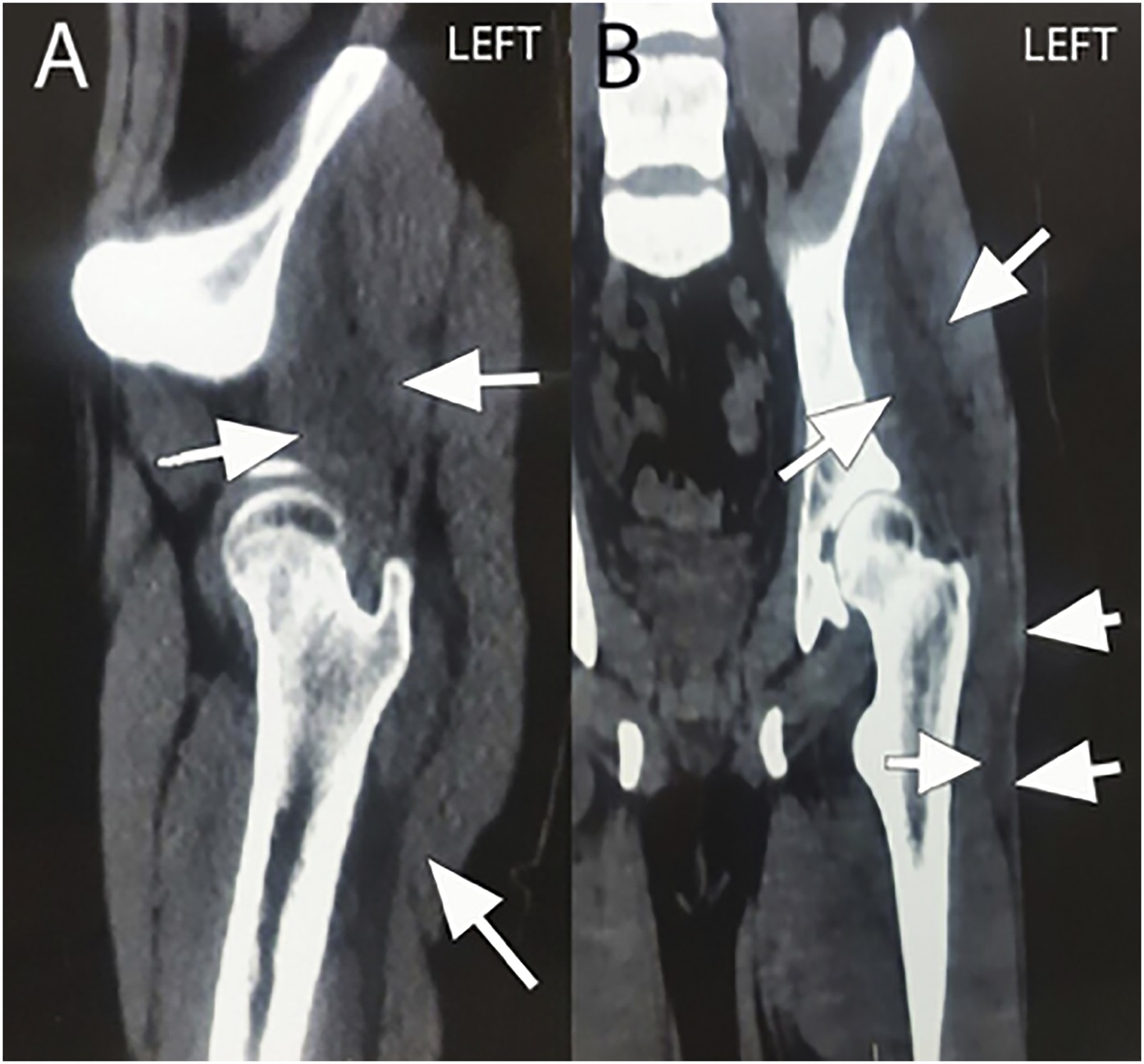

The patient was immunocompetent, a nonsmoker, had no chronic cough, and did not live in an overcrowded condition or belong to a low socioeconomic class. Laboratory values showed an elevated WBC count of 12.8 × 109/L with neutrophilia, an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 49 mm/hr, and an elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) level. Results from a chest radiograph were within normal limits. An ultrasound showed 2 hypoechoic fluid collections with poorly defined irregular borders on the left ASIS: one (120 × 27 × 60 mm in size) extended to the left greater trochanter, and the other (18 × 10 × 19 mm in size) extended to the ipsilateral inguinal region. CT of the pelvis and the thigh demonstrated a punched-out lesion in the left ASIS, bone fragmentation, and poorly defined heterogeneous collections between the gluteus minimus and medius muscles, which surrounded the ipsilateral greater trochanter caudally (Fig. 2).

Decortication and curettage of the left ilium were performed. Specimens were submitted for cytologic analysis, including Gram and acid-fast staining and fungal, bacterial, and mycobacterial culture. Next, we performed profuse lavage and closure with percutaneous drainage. The patient remained hospitalized and was treated with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and clindamycin. The blood cultures and histopathologic analysis that had been performed at the initial hospital were negative and inconclusive.

The symptoms worsened within 72 hours, and the patient experienced night sweats, dehiscence of the surgical wound, and low-grade fevers. Blood tests showed a normal WBC count, an elevated ESR, and an elevated CRP level. The medication was changed to vancomycin and piperacillin.

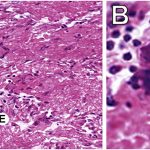

Histopathology is shown in Figure 3.

The patient was diagnosed with necrotizing granulomas suggestive of mycobacterial osteomyelitis.

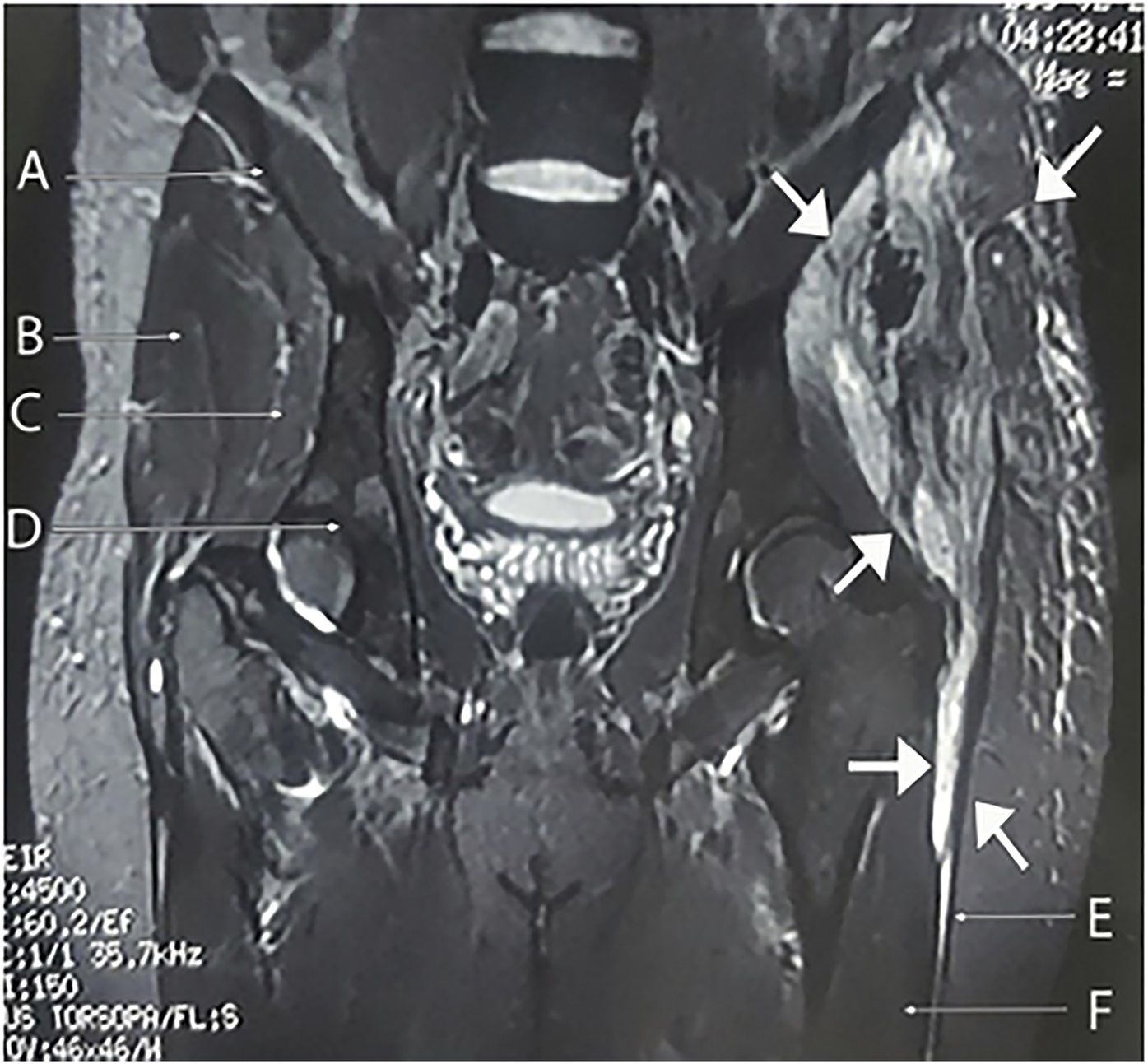

Although the results of acid-fast staining were negative, mycobacteria are the most common etiology for necrotizing granulomas; consequently, while waiting for more results, antitubercular drug (ATD) therapy was started with isoniazid, pyrazinamide, rifampicin, and ethambutol. A CT-guided bone biopsy was performed (obtaining approximately 30 mL of purulent fluid) in order to repeat acid-fast staining, mycobacterial culture, and antimicrobial drug-susceptibility testing. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis showed progression of the osteolytic lesion (Fig. 4).

In early December 2014, a broader incision was made, and we performed drainage, profuse lavage, decortication, and curettage with clearer safety margins. The patient remained hospitalized for the following week with ATD therapy. Although the results of the acid-fast staining were negative, 4 weeks later, the culture results were positive for drug-sensitive Mycobacterium tuberculosis. ATD therapy was continued; there was no pulmonary tuberculosis (TB). However, given that certain areas of Buenos Aires have a high prevalence of TB, the patient’s close contacts were questioned regarding active TB. No contacts were found to be affected.

Once stable, the patient was discharged, and follow-ups were scheduled with the infectious disease and orthopaedic departments. Rapid improvement was evident with ATD and physical therapy. During the first 2 months, the patient received isoniazid, pyrazinamide, rifampicin, and ethambutol; he continued with rifampicin and isoniazid therapy for 10 months.

Over the first week, the patient had gradual remission of the night sweats, malaise, and pain. Throughout the second week, he remained afebrile, with uncomplicated surgical wound-healing, decreasing ESR and CRP level, and an absence of fluid collections. By 3 months, he had no constitutional symptoms, minimal limited thigh abduction, normal infectious parameters, and no evidence of a bone lesion on radiographs. At 12 months, he was asymptomatic and was performing regular activities; the ATD therapy was discontinued. At the 2-year follow-up, he was in complete remission with no signs of TB.

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: Stingo FE, Rodriguez-Fontan F, Burger-Van der Walt E, Arce J, Garcia SN, Munafo RM. Isolated iliac crest tuberculosis: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2018 Apr-Jun;8(2):e31.

Our patient, who had no risk factors, presented with isolated TB of the iliac crest. TB usually presents as a pulmonary infection, but approximately 10% to 20% of cases present as extrapulmonary TB, which affects any other organ system. Skeletal tuberculosis accounts for 10% to 20% of extrapulmonary TB cases, hence 1% to 4% of all TB cases. Iliac crest TB is extremely rare (<1% of skeletal TB) and may mimic other conditions. To our knowledge, there are only a handful of reported cases of iliac crest TB.

Most cases of skeletal TB are spinal osteomyelitis (Pott disease), and arthritis is the next most common; the least common types of skeletal TB are long bone osteomyelitis and Poncet disease. The most common symptom is local pain, which increases in severity over the course of weeks to months; some patients develop decreased range of motion and present with a “cold abscess” and/or a sinus. Considering that grossly 30% to 40% of skeletal TB cases present constitutional symptoms and mostly have an insidious presentation, suspicion for skeletal TB can be low. Bone-pain resistance to analgesics should alert orthopaedic surgeons of infection, neoplasia, or autoimmune conditions.

Plain radiographs may be initially normal or show minimal changes (e.g., osteolysis, osteopenia, sclerosis, periostitis, or cystic lesions). MRI and bone scans are more sensitive studies. However, there is no pathognomonic imaging finding. If the diagnosis of osteomyelitis is uncertain, bone biopsy (percutaneous or open) and/or fine needle aspiration should be performed. It is mandatory to narrow down and confirm the diagnosis and define treatment unless the blood culture specimens are positive for a likely pathogen (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus, a gram-negative rod). If blood and fine needle aspiration cultures are negative and the suspicion persists, a repeat bone biopsy should be performed. Given the insidious onset and broad differential diagnosis of TB, early histopathologic analysis for neoplasia and fungal, bacterial, and mycobacterial infections should be implemented. However, specimens often undergo standard bacterial cultures, while fungal and mycobacterial cultures are done only when these types of infections are suspected. In cases of chronic osteomyelitis or failure to respond to initial empiric therapy, tissue samples should always be subject to fungal, bacterial, and mycobacterial culture. In our patient, the samples were initially analyzed for bacterial pathogens, and he was started empirically on antibiotics. It was not until approximately 3 months of ongoing disease that the diagnosis was confirmed. The average delay from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of skeletal TB is 16 months. Therefore, TB should be considered in the differential diagnosis right from the start in order to commence early treatment and avoid serious complications. Curettage of bone lesions allows better therapeutic results because M. tuberculosis is sequestered in necrotic tissue, and cannot be reached by ATD therapy. Clinical assessment and normalization of inflammatory markers (ESR and CRP level) define the therapeutic duration and response.

In summary, tuberculous osteomyelitis is a diagnostic challenge; it must always be kept in mind because it mimics other musculoskeletal conditions and typically has an insidious presentation. It is usually misdiagnosed, which delays the initiation of treatment. TB must be confirmed histologically or by microbiologic culture. A combination of surgery and ATD therapy can lead to rapid clinical recovery.

Reference: Stingo FE, Rodriguez-Fontan F, Burger-Van der Walt E, Arce J, Garcia SN, Munafo RM. Isolated iliac crest tuberculosis: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2018 Apr-Jun;8(2):e31.

What is the diagnosis?

Sarcoidosis

Langerhans cell histiocytosis

Necrotizing granulomas suggestive of mycobacterial osteomyelitis

Giant cell tumor of bone

Coccidioidomycosis

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3 Fig. 4

Fig. 4