A 44-year-old Venezuelan woman presented with a 2-year history of pelvic, hip, and lower-extremity aching and pain. As a child, she had persistent lower-extremity pain that was interpreted as growing pains. At the age of 18 years, she was diagnosed with dermatomyositis based on a muscle biopsy and electromyographic study. She also had a rash on the face and anterior chest that had fluctuated. The patient was treated for 3 years with 16 mg of methylprednisolone; this medication was then tapered off over a period of 2 years. She remained in remission until the age of 42 years when she developed fatigability and diplopia mainly on the left lateral gaze and 2 months later on the right lateral gaze. She was hospitalized, and extensive laboratory tests, acetylcholine receptor antibody titers, and brain imaging (computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance imaging [MRI], and angiogram) results were unremarkable. She continued having fatigability, muscle stiffness, and weakness going up stairs or with any strenuous activity. Her medical history also included hypertension, hypercholesteremia, gastritis, migraines, and polymyositis. On presentation, she reported diplopia and dizziness, but noted that she did not have constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, or recent weight loss. She was seen by numerous specialists in rheumatology, neurology, and endocrinology before being evaluated by an orthopaedic surgeon. The initial diagnosis by the orthopaedic surgeon was polyostotic disease of uncertain etiology involving the pelvis and both femora.

Family history revealed that the patient’s father had died when she was young, and her sister had similar symptoms. Also, 2 of the patient’s 3 children had begun to report bone pain. Evaluation by genetics led to her family’s participation in our research studies.

Physical examination revealed an alert, oriented woman. The cranial nerves were intact without nystagmus. The patient had full strength of all extremities with a normal gait, normal deep tendon reflexes, and no sensory deficits. Hip range of motion revealed flexion to 100° and internal rotation to 15°. Hip motion was without pain, and impingement signs were negative. A full examination of the lower extremity showed no palpable soft-tissue masses.

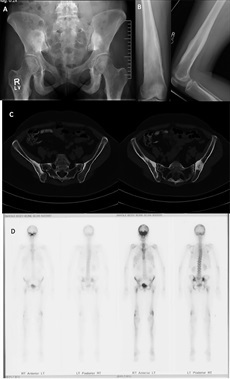

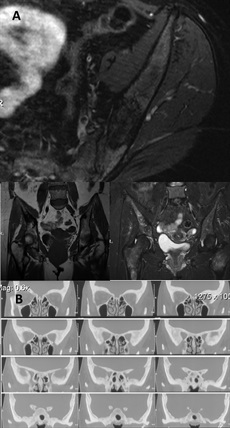

Imaging studies included radiographs of the pelvis and bilateral lower extremities, bone scan, CT scans of the pelvis and orbits, and MRI scans of the pelvis and brain (Figs. 1 and 2). Radiographs revealed hyperostosis and cortical thickening in bilateral proximal and distal parts of the femur. The distal metaphysis of each femur demonstrated an Erlenmeyer-flask shape (Figs. 1-A and 1-B). Radiographs and CT scans revealed hyperostosis and cortical thickening in bilateral posterior ilia (Figs. 1-A and 1-C). Bone scans displayed increased activity in the anterior cranial fossa, bilateral posterior ilia, and proximal and distal parts of the femora (Fig. 1-D). MRI scans of the pelvis showed marrow edema within the proximal femoral diaphysis, extending into the femoral neck at the level of the lesser trochanter with diffuse cortical thickening (Fig. 2-A). Radiographs of the hands and feet revealed thickening of proximal phalanges and metatarsal cortical thickening. The CT scans of the orbits revealed a thickened appearance of the frontal facial bone indicating hyperostosis frontalis internus and thickening of the base of the skull (Fig. 2-B). Brain MRI scans revealed normal brain architecture except for cranial base thickening. Laboratory studies revealed elevated alkaline phosphatase, liver enzymes, and cholesterol. The patient was found to have anemia and decreased vitamin D levels. Her thyroid hormones were normal, and analysis for heavy metals was negative.

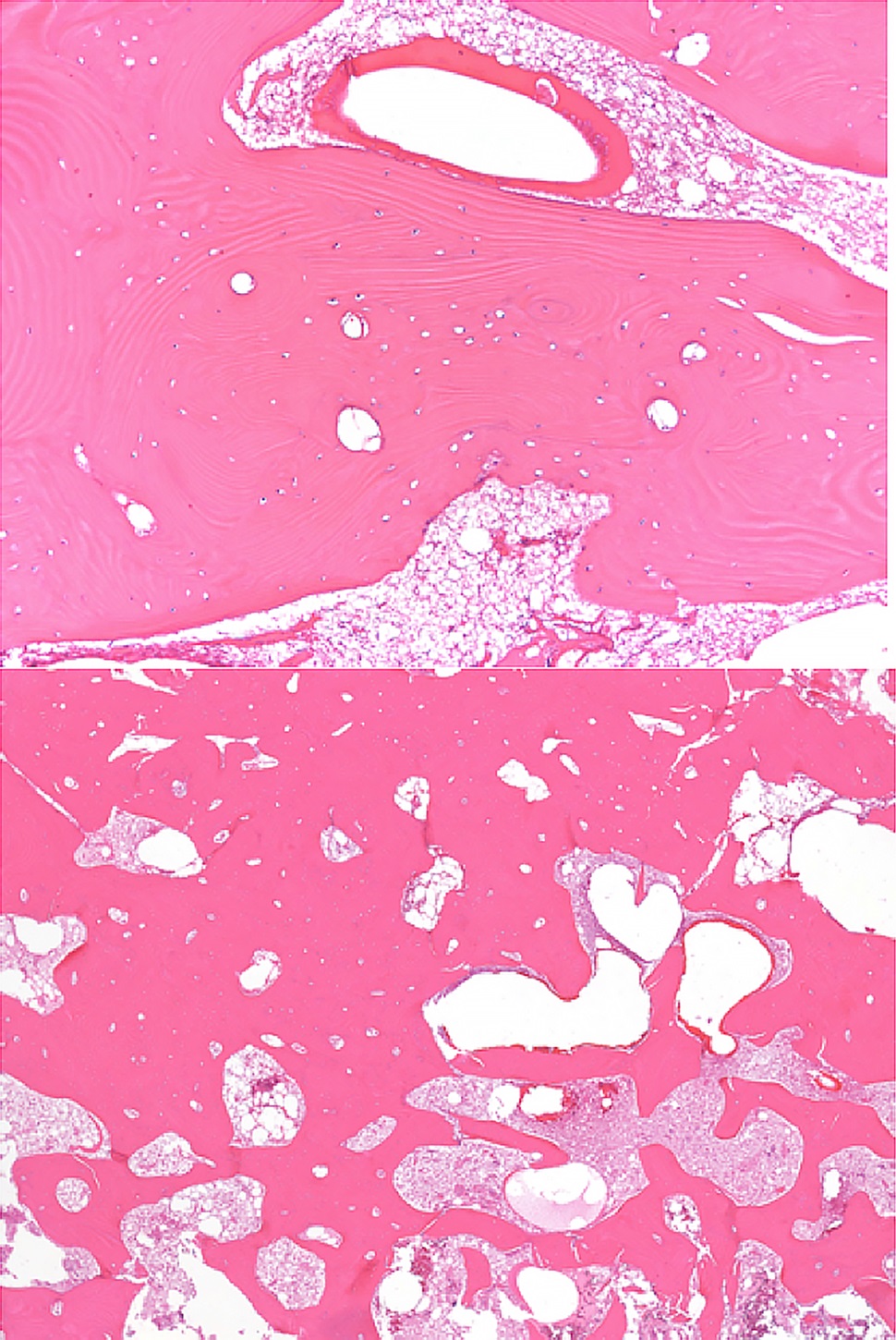

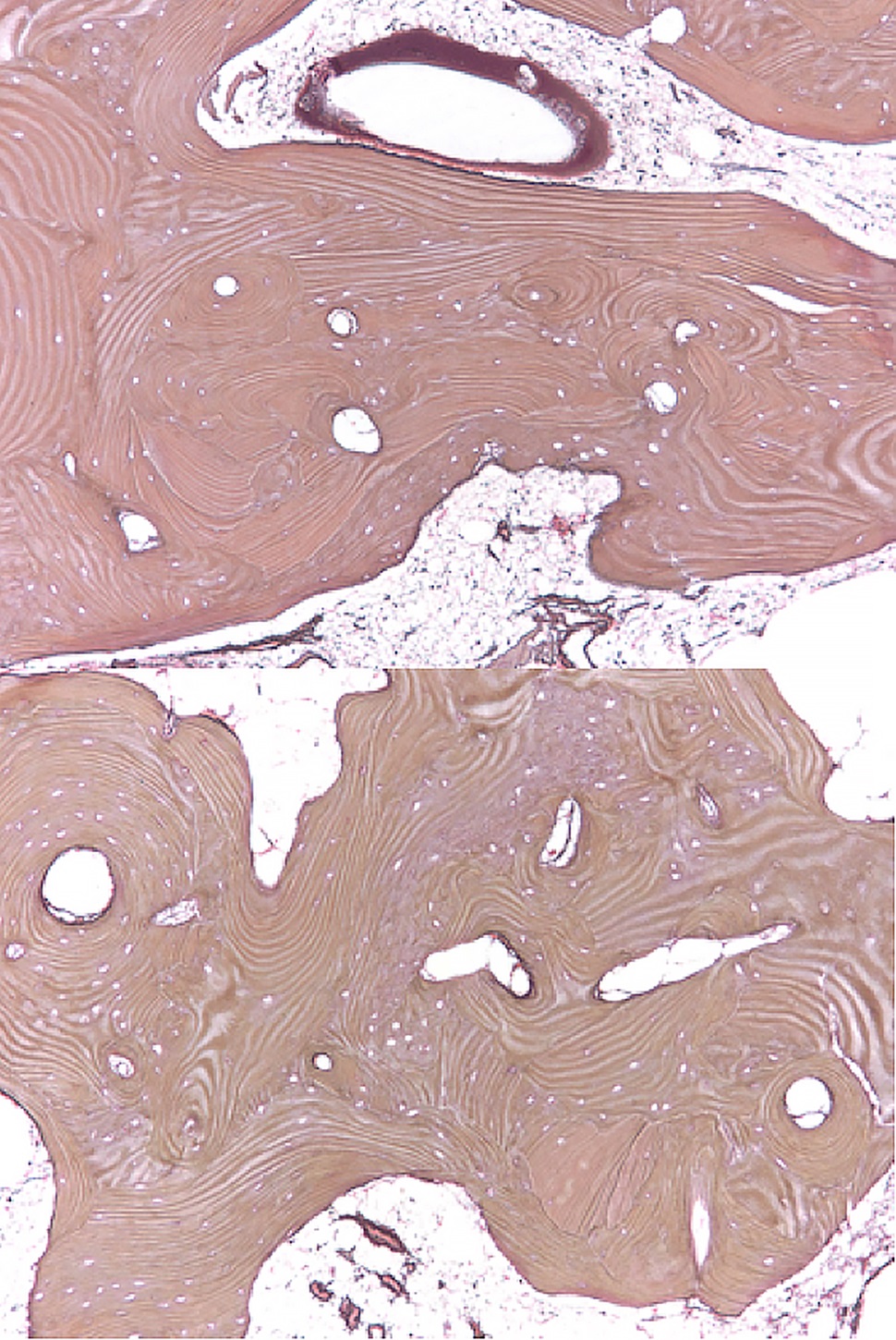

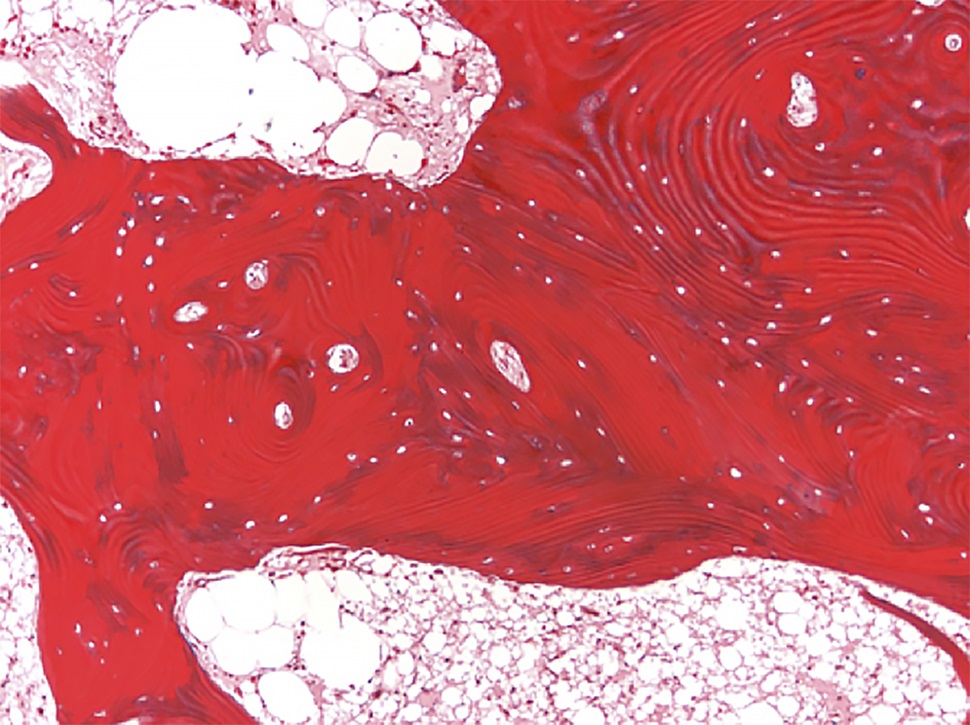

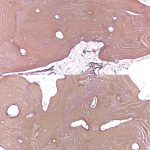

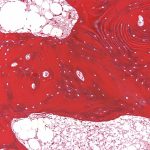

Bilateral posterior iliac crest bone biopsies were performed using a Michel needle and showed localized sclerosis of the medullary cavity with abundant lamellar and focal woven bone that had a cortical-like pattern, focal marrow fibrosis, and mild chronic inflammation (Figs. 3, 4, and 5). The initial treatment included standard doses of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (naproxen 500 mg 2 times daily orally as required, tramadol 50 mg once daily, and 650-mg acetaminophen), 100-mg propoxyphene tablets sparingly for pain, sertraline 50 mg daily for depression, metoprolol 100 mg daily for hypertension, and standard bisphosphonates for presumed Paget disease of bone. Unfortunately, these did not provide substantial relief. The patient continued to have worsening diplopia, craniocervical pain, depression, and diffuse musculoskeletal pain in the extremities.

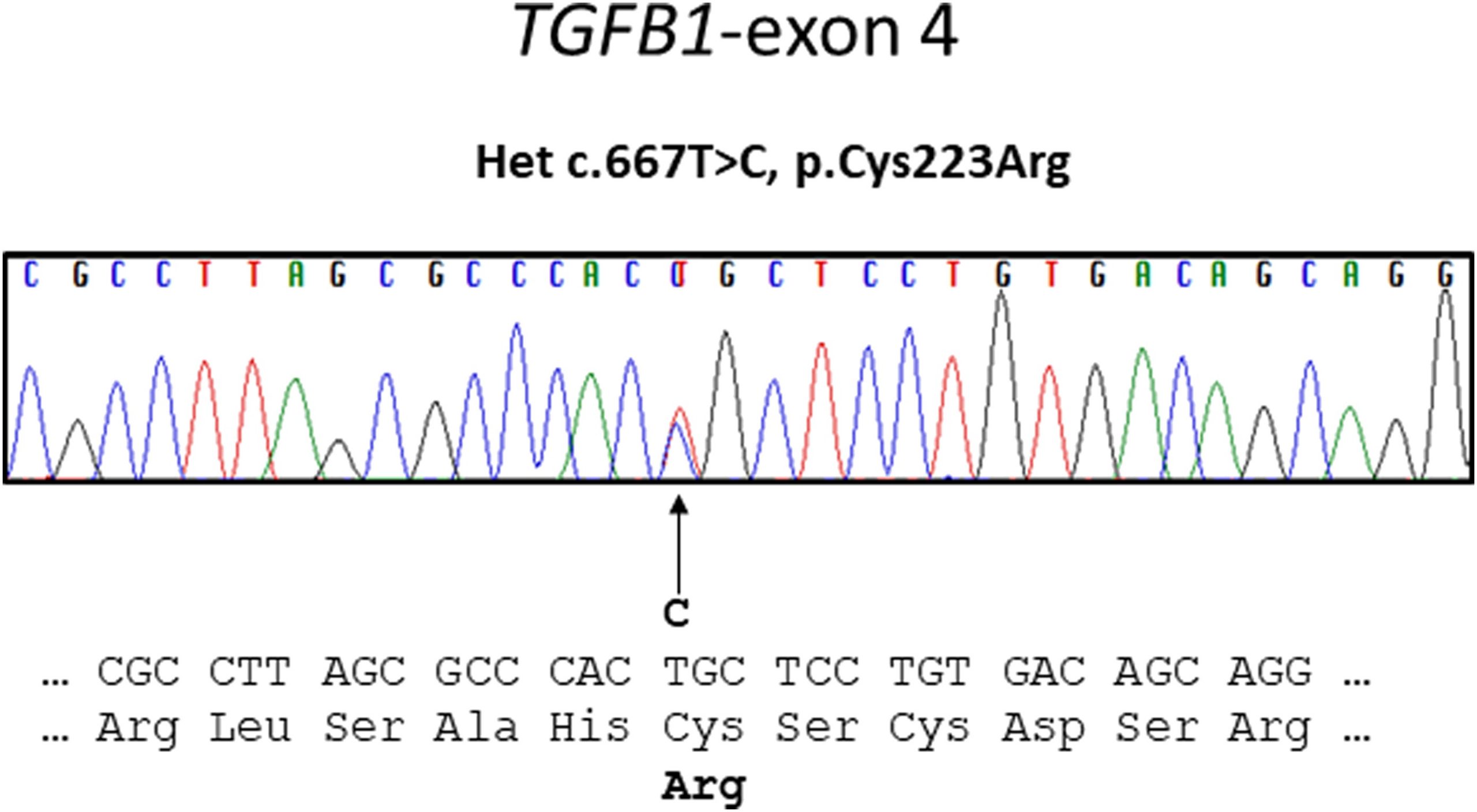

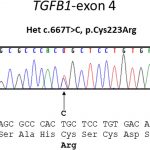

A sclerotic bone dysplasia workup with sequencing of the transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB-1) gene located on chromosome 19q13 revealed a heterozygous missense variant in exon-4.

The combination of clinical, imaging, and molecular testing led to the diagnosis of progressive diaphyseal dysplasia (Camurati-Engelmann disease).

All 7 coding exons and adjacent messenger RNA (mRNA) splice sites of the TGFB-1 gene were amplified by polymerase chain reaction and sequenced as previously described. A heterozygous missense mutation (c.667T>C, p.Cys223Arg) in exon 4 of TGFB-1 was identified (Fig. 6).

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: Owhonda RA, Wells JE, Lloyd EW, Mumm S, Kimonis V. A case report of a 44-year-old woman with Camurati-Englemann disease: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020 Jul-Sep;10(3):e19.00400.

Camurati-Engelmann disease is a rare disease associated with bone dysplasia mainly affecting the skull and the diaphyses of the long tubular bones associated with mutations in the TGFB-1 gene. This case is unique in that the presentation was relatively late in life and the symptoms were delayed.

This case is unique also in that it reveals the heterozygous missense mutation (c.667T>C, p.Cys223Arg) in exon 4 of TGFB-1 as the cause of Camurati-Engelmann disease in this patient. This mutation has only been mentioned once previously in the literature. Kinoshita et al. found 2 novel TGFB-1 mutations in 2 Japanese families, c.667T>C (C223R) and c.667T>G (C223G) both at nt 667, these variants being associated with classic Camurati-Engelmann disease.

Once a diagnosis of Camurati-Engelmann disease is made, the initial evaluation should include full neurologic and cranial examinations, complete skeletal survey, bone scan, complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), hearing screen, and ophthalmologic evaluation. If acute bone pain is present, ESR and a bone scan may be helpful to assess disease activity. Exacerbations in disease activity may correlate with an increase in bone scan activity.

Reflecting on this case, the patient history and the finding of bone pain for extended periods should have triggered consideration of Camurati-Engelmann disease. The transition from imaging studies to a genetic study should be initiated much earlier during patient care allowing for physicians to monitor the patient through regular screenings to assess disease progression on diagnosis. Camurati-Engelmann disease is known to be progressive and can threaten the ability to see and walk normally as the disease progresses.

Currently, there is no known cure for Camurati-Engelmann disease. Treatment options involve symptomatic control of pain with corticosteroids and NSAIDs. Several investigators have reported success with corticosteroids by reducing pain and weakness while improving gait, exercise tolerance, and flexion contractures in addition to correcting anemia and hepatosplenomegaly. Craniectomy is a potential management technique to alleviate compressive cranial nerve symptomology, yet little research has been performed on improving diffuse skeletal pain.

Bisphosphonates have also been shown to reduce bone reabsorption; however, several authors have shown conflicting outcomes in Camurati-Engelmann disease from administration of bisphosphonates, ranging from subtle improvements to worsening of bone pain. Another current treatment option is losartan, which has anti-TGFB-1 effects. It may be helpful in patients who cannot tolerate corticosteroids or as an adjunct in patients using corticosteroids who have concomitant hypertension, although, as far as we know, no studies exist evaluating the effectiveness of losartan for the treatment of Camurati-Engelmann disease. None of the standard treatments provided substantial relief of symptoms for our patient.

This case report offers insight into a novel TGFB-1 gene variant associated with Camurati-Engelmann disease. It details the presentation, diagnosis, current standard of care in medical practice today, and approaches to treatment and their efficacy of this rare sclerotic disease. Traditional methods of treating the symptoms of Camurati-Engelmann disease did not offer substantial relief in this patient, which may be attributable to her specific variant. Limitations of the study included the rarity of this disorder and the report of only 1 other case in the literature with the same variant. This case report expands the typical phenotype associated with Camurati-Engelmann disease in association with the c.667T>C, p.Cys223Arg variant.

Reference: Owhonda RA, Wells JE, Lloyd EW, Mumm S, Kimonis V. A case report of a 44-year-old woman with Camurati-Englemann disease: a case report. JBJS Case Connect. 2020 Jul-Sep;10(3):e19.00400.

What is the diagnosis?

Osteopetrosis

Hyperostosis corticalis generalisata (van Buchem disease)

Vitamin D-resistant rickets

Osteopathia striata (Voorhoeve disease)

Progressive diaphyseal dysplasia (Camurati-Engelmann disease)

Fig. 1

Fig. 1 Fig. 2

Fig. 2 Fig. 3

Fig. 3 Fig. 4

Fig. 4 Fig. 5

Fig. 5 Fig. 6

Fig. 6