A Forty-four-Year-Old Man with an Enlarging Shoulder Mass

December 21, 2011

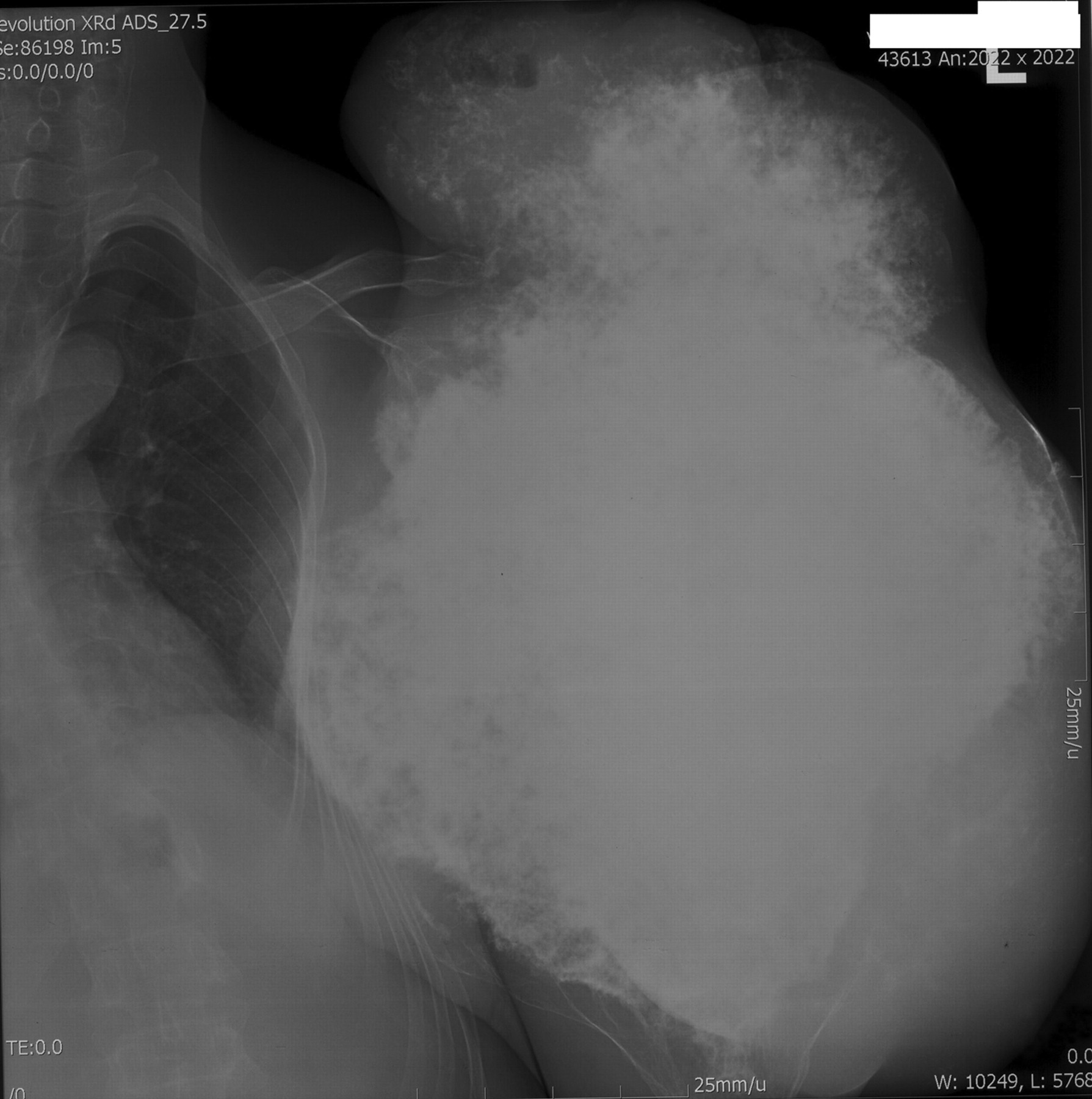

A forty-four-year-old man presented with a twenty-five-year history of a slowly growing, painless mass in the left upper arm. When he was nineteen years old, radiographs of the left humerus had demonstrated a small lesion, with an appearance consistent with the diagnosis of an osteochondroma. As his mild shoulder symptoms completely resolved in a few weeks, no additional treatment was recommended. The patient had no family history of masses or genetic diseases and had not received any treatment until he was admitted to our hospital. On physical examination, a firm, nontender, well-circumscribed, solid, immobile mass of 56.5 × 65.0 × 45.0 cm was noted in the left upper arm and shoulder (Figs. 1 and 2). He had limitation of motion of the left shoulder with normal motion of the left elbow and wrist. Sensation in the left upper extremity was intact. No other bone masses were found in any other body location. Serum alkaline phosphatase and acid phosphatase levels were normal. An incisional biopsy of the mass was obtained.

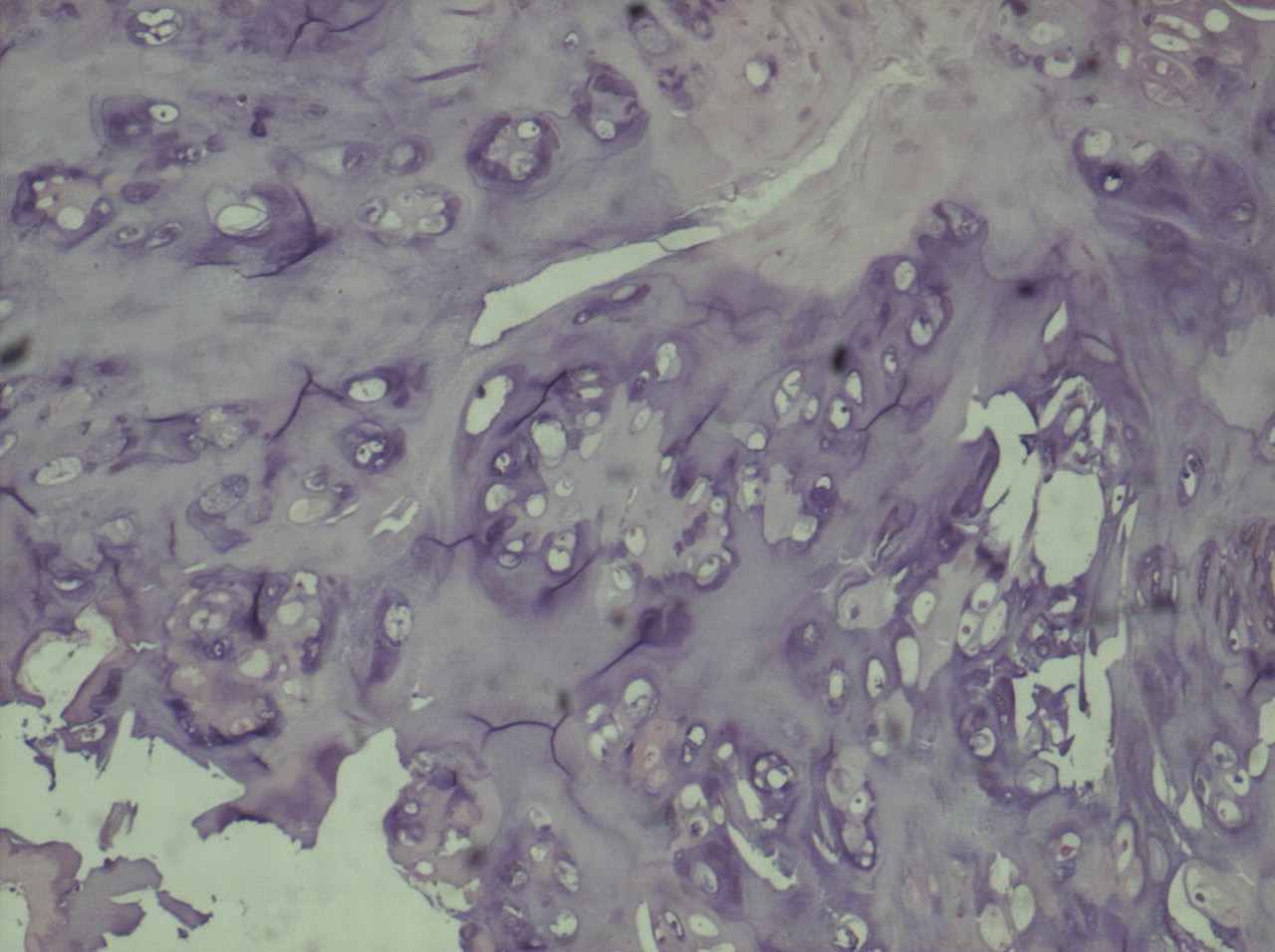

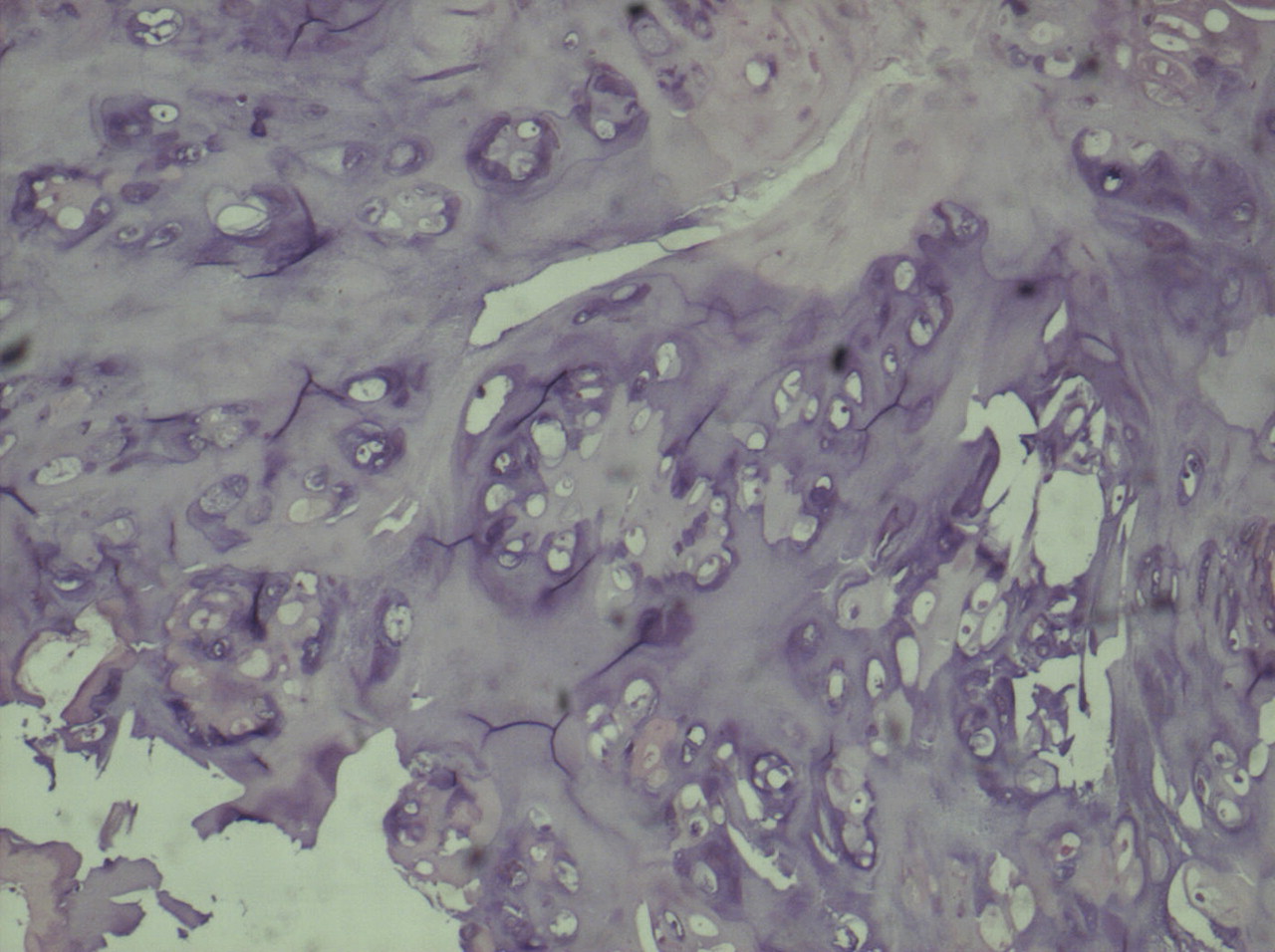

Even though the lesion appeared to be benign, its large size and limited local medical resources prohibited limb-sparing surgery so an amputation was performed. Histological evaluation of the lesion demonstrated that the base of the osteochondroma was in the anteromedial aspect of the humeral cortex. The thickness of the cartilage cap ranged from 3 mm to 2.0 cm, and no atypical cells were seen (Fig. 3).

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: Liu T, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Peng D, Guo X. Enlargement of a humeral osteochondroma after skeletal maturity. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93:e20(1-4).

D’Ambrosia and Ferguson produced exostoses in experimental animals, and their findings supported the concept that osteochondromas are developmental growth defects of the physis. An osteochondroma develops when physeal cells are extruded laterally and proliferates into an exostosis. Therefore, an osteochondroma can arise in any bone that undergoes endochondral ossification and usually stops growing when the physes close. Slow enlargement of an osteochondroma after skeletal maturity has been documented. Lange et al. reported that a small amount of growth can occur after physeal closure and that such late growth may even be common in the natural course of an osteochondroma. Most osteochondromas, however, undergo very little, if any, growth after maturity, and it is generally accepted that substantial growth of an osteochondroma after physeal closure should be a cause for concern about possible malignant transformation of the lesion. One to two percent of solitary osteochondromas undergo malignant transformation into chondrosarcomas. Other reasons for apparent growth of an osteochondroma include the development of a pseudoaneurysm or a bursa overlying the osseous mass. Although malignant transformation to a chondrosarcoma may occur, Krieg et al. reported extensive growth of an osteochondroma in a skeletally mature patient whose tumor was proven to be benign on histological examination. Nogier et al. reported a similar case in an adult with a solitary osteochondroma of the calcaneus. Chondrosarcoma arising in an osteochondroma is often a well-differentiated tumor that is histologically similar to the cartilaginous cap with increased chondrocyte cellularity and cytologic atypia. Extensive myxoid changes are classically absent, so the diagnosis of chondrosarcomatous transformation of an osteochondroma is based mostly on the architecture of the cartilaginous cap and not on its thickness. In the case of malignant transformation, the architecture of the cartilage cap of the osteochondroma is modified, destroyed by thin fibrous septa, resulting in the appearance of a lobulated architecture at low magnification. Some cartilaginous tumor lobules may come away from the cap and invade the peripheral soft tissues. In our patient, the thickness of the cartilage cap ranged from a few millimeters to 2.0 cm, but the cartilage architecture was conserved, with no evidence of tumor extension into the adjacent soft tissue. We have no definitive explanation for the remarkable growth of the lesion in our patient, other than benign enchondral growth of an exostosis after skeletal maturity. Although extensive growth of an osteochondroma after completion of skeletal growth usually heralds malignant change, it is possible that late growth of a benign lesion is more common than is generally recognized, as exemplified by our case.

Reference: Liu T, Zhang X, Zhang Q, Peng D, Guo X. Enlargement of a humeral osteochondroma after skeletal maturity. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011; 93:e20(1-4).

Osteochondroma

Chondrosarcoma

Osteosarcoma

Ewing sarcoma

1

1 2

2 3

3 3

3