An Eleven-Year-Old Boy with a Draining Wound on the Left Elbow

December 3, 2014

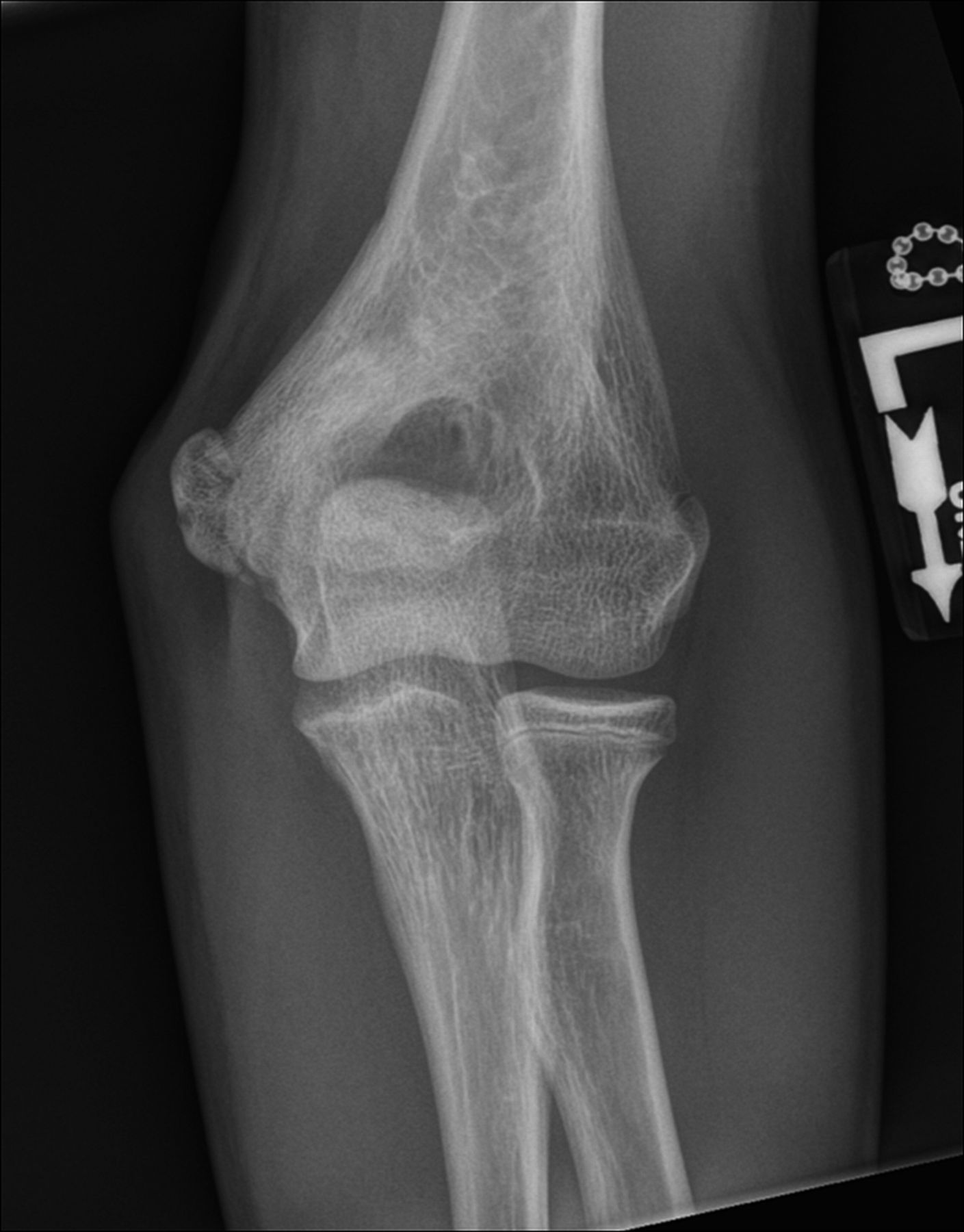

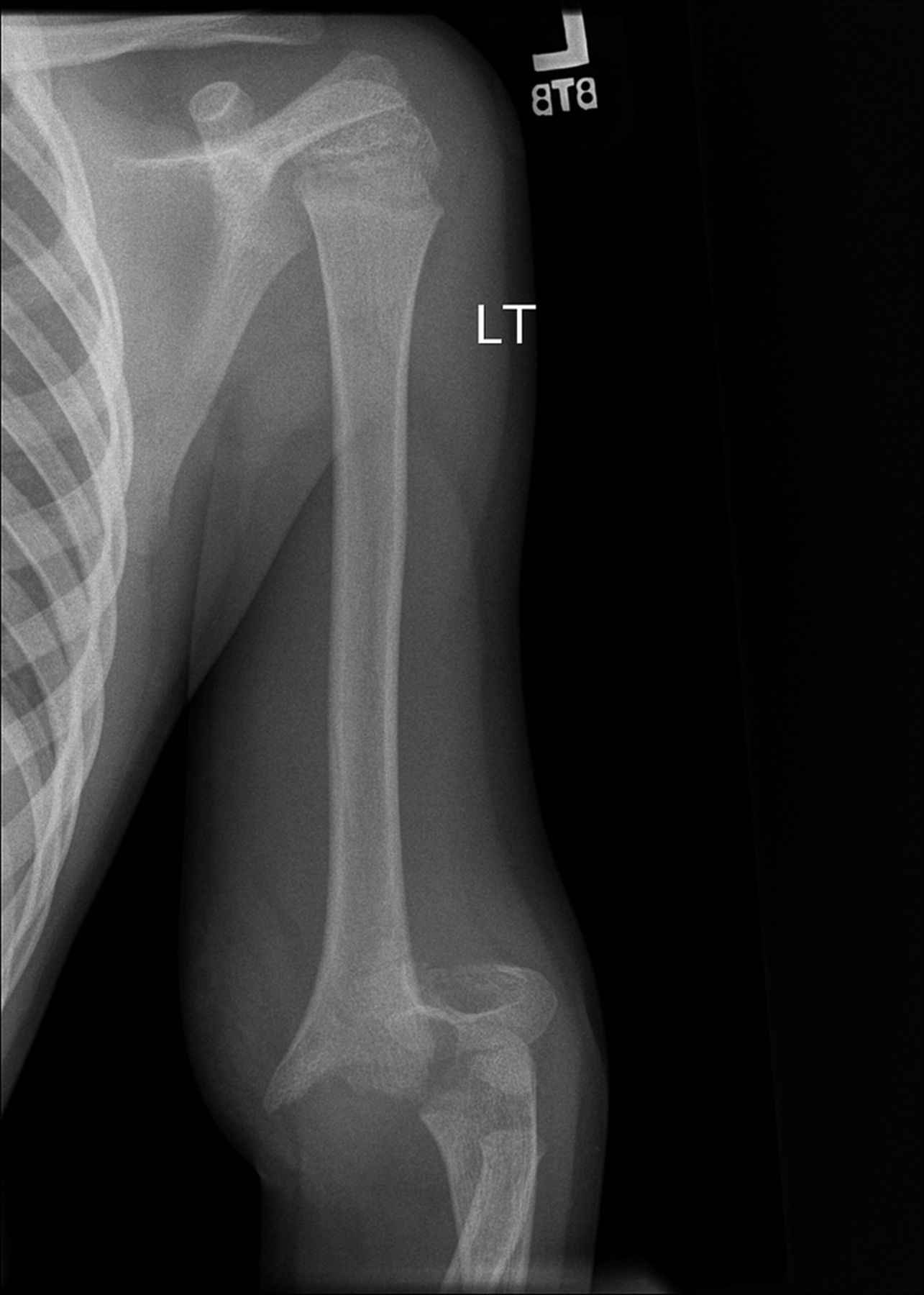

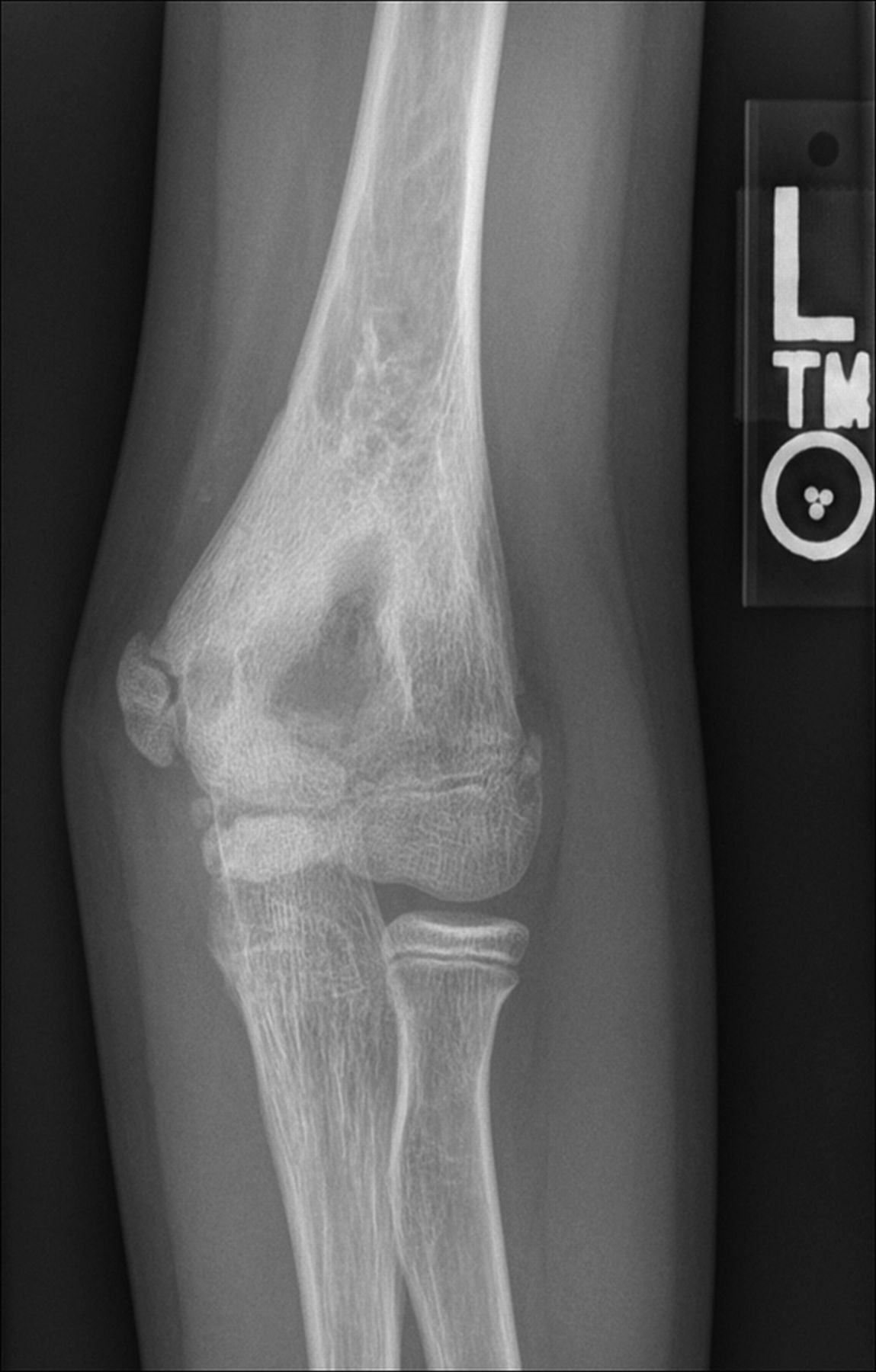

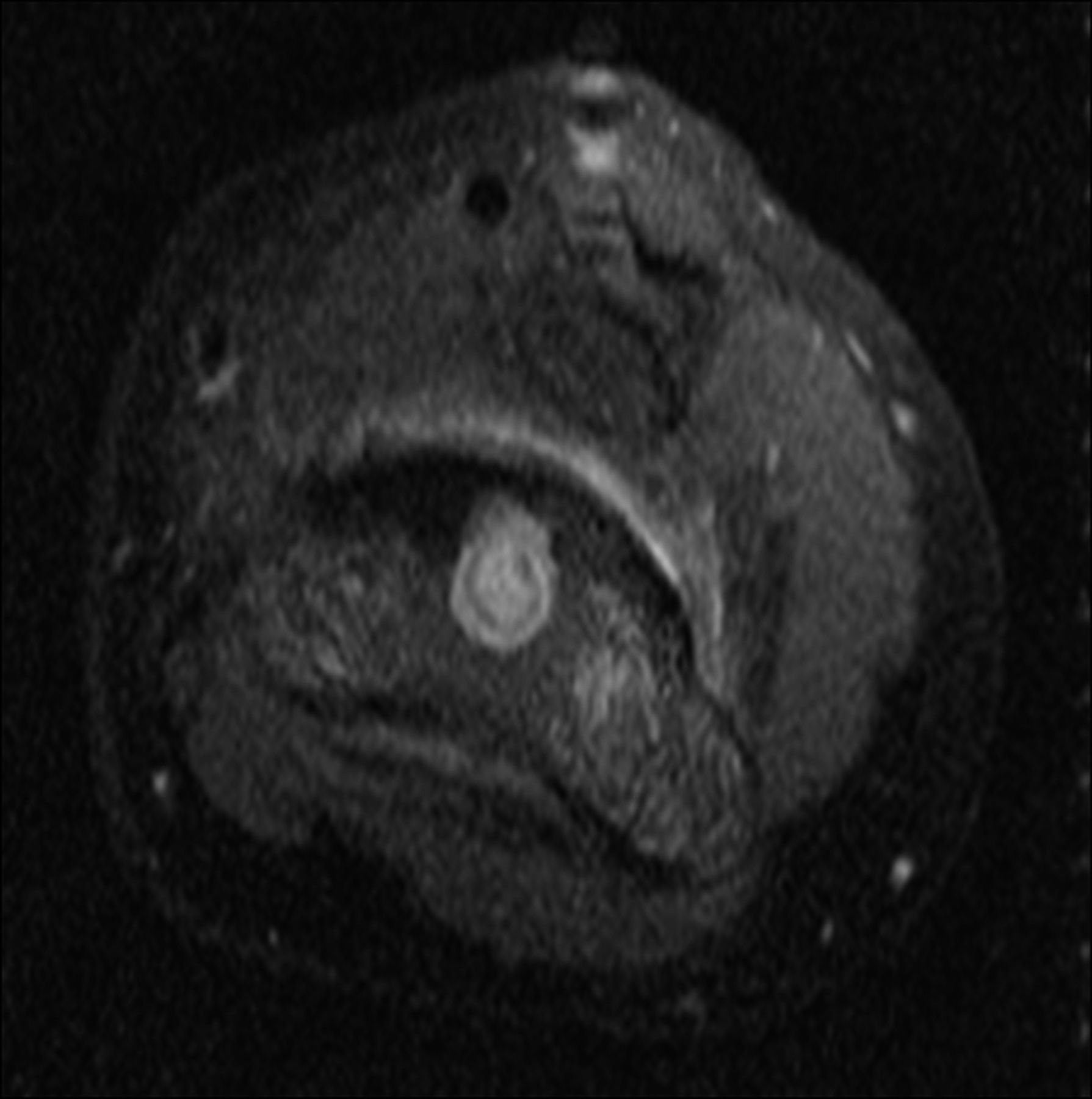

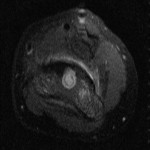

A healthy eleven-year-old right-hand-dominant boy presented to our clinic with a four-week history of a draining wound from the left elbow. The patient had previously had a closed left supracondylar fracture of the humerus that had been treated at our institution with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning when he was five years old. One lateral and one medial pin had been utilized to stabilize the fracture (Figs. 1-A through 1-D). The treatment course had been uncomplicated, and there had been no evidence of pin-site infection. There was no history of erythema or drainage, and the pins had been pulled at one month after surgery. The fracture had healed uneventfully, and he had regained full range of motion of the elbow. At nine years of age, the patient began to notice symptoms of decreased range of motion, pain, and locking in the left elbow following activity (Figs. 2-A and 2-B). The elbow briefly was treated in a long arm cast, followed by a course of occupational therapy for a suspected overuse injury of the elbow. At eleven years of age, the patient began noting fullness along the medial aspect of the elbow, as well as vague symptoms of “tingling” in the arm. Examination by the treating surgeon revealed no tenderness to palpation and full painless elbow range of motion. Radiographs demonstrated increased sclerosis on the medial column of the distal part of the humerus (Figs. 3-A and 3-B). A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study demonstrated postsurgical changes as well as two lucent areas in the distal part of the humerus (Figs. 4-A and 4-B). The patient was referred to our clinic for treatment. In the intervening time, he had developed a draining wound (1 cm in size) from the medial aspect of the elbow (Fig. 5).

Irrigation and debridement of the distal part of the humerus and a biopsy were performed. The lucent areas noted on imaging did not connect when irrigated, and the patient was diagnosed with chronic osteomyelitis. The patient was started on intravenous clindamycin postoperatively. Intraoperative cultures grew methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was switched to oral cephalexin for a total of twelve weeks. At the twelve-month follow-up, he was asymptomatic and was regaining full range of motion of the elbow with no symptoms of locking or catching. Imaging at this time demonstrated that the distal part of the humerus was reconstituted with no evidence of lysis along the medial column (Figs. 6-A and 6-B).

Proceed to Discussion >>Reference: Pulos N, Carrigan RB. Osteomyelitis as a late complication of percutaneous pinning of a supracondylar fracture of the distal part of the humerus. JBJS Case Connect. 2014 Oct 22;4(4):e99.

Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of supracondylar distal humeral fractures is one of the most common procedures in pediatric fracture care. It is a safe and effective procedure for the treatment of these injuries and has a low rate of complication. Iobst et al. reported no infections in 304 cases. Bashyal et al. noted only six infections in 622 fractures that had been treated with this technique. Only one patient developed septic arthritis and associated osteomyelitis that required surgical irrigation and debridement and intravenous antibiotics at a mean follow-up of forty weeks. In addition to a thorough history and physical examination, imaging studies play an important role in the diagnosis of infection. Schatzker et al. demonstrated that necrosis of osteocytes surrounding screw holes is caused by the drilling of the hole. The cellular damage can extend 0.5 to 1.0 mm from the hole. The use of percutaneous pins may exacerbate this tissue necrosis via thermal energy that is incurred during insertion. Replacement of this necrotic bone with living osseous tissue occurs via osteoclastic resorption and new bone formation. This results in the typical radiographic appearance of sclerotic bone adjacent to the pin track. A surrounding radiolucent zone of bone destruction, representing granulation tissue, is associated with infection. Our patient’s radiographs were concerning for infection; however, the use of MRI has greatly increased the sensitivity of medical imaging to detect an infection of osseous and nonosseous tissues. Chronic osteomyelitis in pin tracks has been well reported as a complication after external fixation and skeletal traction. In Green and Ripley’s series of fourteen patients, the majority of pin-track osteomyelitis infections were caused by S. aureus and were treated with curettage and intravenous antibiotics. Time from fixation to debridement ranged from one month to sixty months. The delayed onset of a quiescent pin-track infection is reported even less. Mishra and Perkins described a pediatric patient with closed fracture of the femur who had been treated with external fixation and had developed discharge from a pin track ten years later. Although radiographs and a white blood-cell localization scan did not reveal bone infection, the authors attributed the soft-tissue pin-track infection to osteomyelitis. Walter and Cramer reported on a similar case of a closed femoral fracture that had been treated with external fixation and had developed a free-floating ring sequestrum. The patient was asymptomatic for two years prior to presenting with signs and symptoms of infection. Cultures grew methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, and the patient was successfully treated with curettage, removal of the loose ring sequestrum, and antibiotics. Courvoisier et al. reported on two pediatric patients with lower limb fractures who had been treated with skeletal traction and had presented twenty-two years and twenty-five years later with chronic osteomyelitis. In both cases, the infecting organism was a sensitive strain of S. aureus. Both cases were successfully treated with curettage and antibiotic treatment for three months. In our patient and in the patients described above, the microorganism responsible for infection was a sensitive strain of S. aureus. While gram-negative bacteria are more virulent and more likely to cause recurrence, S. aureus is known to be responsible for the formation of chronic abscesses. Antibiotic treatment length is controversial. In addition to surgical irrigation and debridement, our patient was successfully treated with twelve weeks of antibiotics, similar to other published reports. In conclusion, pin-track infections are a known complication of external fixators and skeletal traction, but they are rarely seen in the treatment of supracondylar humeral fractures. The present case demonstrates that infected pin-tracks as a result of closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of supracondylar humeral fractures can lie dormant with the potential for later reactivation. The diagnosis of this unusual complication was confirmed with an MRI scan. We conclude that dormant osteomyelitis should be considered in the differential diagnosis for any child who presents with elbow symptoms and a prior history of supracondylar humeral fracture that has been treated with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning.

Reference: Pulos N, Carrigan RB. Osteomyelitis as a late complication of percutaneous pinning of a supracondylar fracture of the distal part of the humerus. JBJS Case Connect. 2014 Oct 22;4(4):e99.

Inclusion cyst

Squamous cell carcinoma

Chronic osteomyelitis of the distal part of the humerus

Synovial cell sarcoma of the elbow

Retained foreign body

Fig. 1-A

Fig. 1-A Fig. 1-B

Fig. 1-B Fig. 1-C

Fig. 1-C Fig. 1-D

Fig. 1-D Fig. 2-A

Fig. 2-A Fig. 2-B

Fig. 2-B Fig. 3-A

Fig. 3-A Fig. 3-B

Fig. 3-B Fig. 4-A

Fig. 4-A Fig. 4-B

Fig. 4-B Fig. 5

Fig. 5 Fig. 6-A

Fig. 6-A Fig. 6-B

Fig. 6-B